[温故知新]、、

茶の本

(岡倉天心)、

武士度(新渡戸稲造)、

代表的日本人(内村鑑三)、

学問のすすめ(福沢諭吉)、

自助論(Smiles)、

『 西郷(Saigo) 隆盛(Takamori) 』

Japan and The Japanese(代表的日本人) -Uchimura Kanzo(内村鑑三)-

Book(Read)(YouTube)、、

西郷百科

(english)

検索

・Saigo Takamori(All)

(Videos)

(Images)

(YouTube),、

・西郷隆盛(検索),

(動画),

(YouTube),、

【西郷隆盛――新日本の創設者】内容抜粋 志士の言葉 [朗読試聴]

「天の道を行うものは、世のなかすべてが非難しても卑下せず、世のなかすべてが口をそろえて褒め称えてもおごりはしない」

「天を相手にして、人を相手にするな。何ごとも天のために行え。人をとがめず、己の誠の足りないところを探せ」

「人は自分に克つことによって成功し、自分を愛することによって失敗する。八分どおりうまく行きながら、最後の二分で失敗する人が

多いのはなぜか。それは、成功が見えてくるにつれて、自分を愛する心が育ってくるからである。警戒心が去り、

安楽を求める気持ちが戻ってきて仕事が煩わしくなり、そして失敗する」

「機会には2つの種類がある。求めずして来る機会と、自ら作り出す機会である。世のなかで機会と呼ばれるのは往々にして求めずして来る機会である。

しかし真の機会は、理に従って行い、時勢に従って動くことによって生まれる。重要な局面では、機会は自分の手で作り出さねばならない」

「どんなに手段や制度を論じても、それを行う人がいなければ何もならない。人がまずあって、その後に手段が来る。人こそが一番の宝であり、われわれは皆そんな人間になれるよう心がけなくてはならない」

Saigo Takamori - A, Founder of New Japan【西郷隆盛――新日本の創設者】

I-The Japanese Revolution of 1868 (第1章 1868年 日本の維新革命)、

II-Birth, Education, and Inspiration(第2章 生い立ちと教育、そして天の声)、

III-His, Part in the Revolution(第3章 維新において西郷が果たした役割)、

IV-The, Corean Affair(第4章 朝鮮の議)、

V-Saigo, as a Rebel(第5章 逆賊・西郷)、

VI-His, Ways of Living and Views of Life(第6章 その生活と人生観)

・内村鑑三「代表的日本人-西郷隆盛」 (朗読1、

2、

3、

4、

5、

6、

7、

8、

9、)

SAIGO TAKAMORI - A FOUNDER OF NEW JAPAN

I -THE JAPANESE REVOLUTION OF 1868

WHEN Nippon first, at Heaven's command, arose from the azure main, this was

the charge to the land: "Niphonia, keep within thy gates. Mingle not with the world

till I call thee forth." So she remained for two thousand years and more, her seas

unplowed by the fleets of the nations, and her shores free from their defilement.

That is a most unphilosophical criticism that condemns Japan for her long

seclusion from the world. Wisdom higher than all wisdoms has ordered it so, and

the country was better for having remained so, and the world was, and is, to be

better for her having been kept so. Inaccessibility to the world is not always a curse

to a nation. What benignant father would have his children prematurely thrown

into the world that they might come under its so-called "civilizing influences"?

India with her comparative accessibility to the world became an easy prey to

European selfishness. What did the world with Inca's empires and Montezuma's

peaceful land? They condemn us for our seclusion. We open our gates, and Clives

and Corteses are let loose upon us. Do not armed burglars do the same when they

break into a well-locked house?

Providence was kind therefore in locking us up from the world with seas and

continents on all sides; and when greed more than once tried to force its way into us

before our appointed time came, it was our genuine instinct of self-defence that

refused to open our gates to the world. Our national character was to be fully

formed that the world might not swallow us up when we come in contact with it,

and make of us an amorphous something without anything special to call our own.

Then the world too needed further refinement, before it could receive us into its

membership. I think the Japanese Revolution of 1868 signifies a point in the

world's history when the two races of mankind representing the two distinct forms

of civilization were brought to honourable intercourse one with the other, when the

Prospective West was given a check in its anarchic progress, and the Retrospective

East was wakened from its stagnant slumber. From that time on, there were to be

neither Occidents nor Orients, but all to be one in humanity and righteousness.

Before Japan awoke, one part of the world turned its back to the other. By her and

through her, the two were brought face to face. Japan is to solve, and is solving, the

question of the right relation of Europe with Asia.

So our long seclusion was to end, and men and opportunities were needed to bring

it to an end. China and California on the opposite banks of the Pacific opened at

about the same time, there came a necessity for opening Japan to bring the two

ends of the world together. This was an external opportunity. Internally, the last

and greatest of the feudal dynasties was losing its power, and the nation, tired of

separation and mutual animosities within, felt, for the first time in its history,

importance and desirability of union. But man makes and uses opportunities. I

consider Matthew Calbraith Perry of the United States Navy to be one of the

greatest friends of humanity the world has ever seen. In his diaries we read that he

bombarded the shores of Japan with doxologies, and not with ordnance.* [ See

Narrative of Expedition of the American Squadron to the Chinese Seas and Japan

by Commondore Perry.] His mission was a delicate one of waking up a hermit

nation without doing injury to its dignity, yet keeping its native pride at bay. His

was the task of a true missionary, done with Heaven's gracious help, with many an

invocation to the Ruler of nations. Thrice blessed is the land that had a Christian

commodore sent to it to open it to the world. - To a Christian admiral knocking

from outside, there responded a brave upright general, a "reverer of Heaven and

lover of mankind" from within. The two never saw each other in their lives, and we

never hear of one complimenting the other. Yet we their biographers do know that

despite all the differences in their outward garments, the souls that dwelt in both

were of kindred stuff. Unwittingly they worked in concert, one executing what the

other had initiated. So does the World-Spirit weave his garment of Destiny,

underneath the vision of purblind mortals, yet wonderful to the eye of the

thoughtful historian.

Thus we see that the Japanese Revolution of 1868, like all healthful and

permanent revolutions, had its origin in righteousness and God-made necessity.

The land that had been obstinately closed against greed, opened itself freely

toward justice and equity. Self-sacrifice of the rarest kind, based upon a voice from

the innermost depth of soul, did Bins open its doors to the world. They therefore

sin against the height of the heavens who seek self-aggrandizement in this nation,

as do they also who mistake its high-calling, and allow it to be trampled by the

mammon of this world.

II -BIRTH, EDUCATION, AND INSPIRATION

"The Great Saigo," as he is usually called, both for his greatness and to

distinguish him from the younger Saigo, his brother, was born in the 10th year of

Bunsei (1827) in the city of Kagoshima. A stone-monument now marks the spot

where he first saw light, now far from the place where his illustrious colleague,

Okubo, was born two years later, which is also so marked. His family had no

hereditary fame to boast of; only "below middle" in the large han of Satzuma. He

was the eldest of six children, - four brothers and two sisters. In his boyhood there

was nothing remarkable about him. He was a slow, silent boy, and even passed for

an idiot among his comrades. It is said that his soul was first roused to

consciousness of duty by witnessing one of his distant relatives committing

harakiri in his presence, who told the lad just before he plunged a dagger into his

belly, of the life that should be devoted to the cause of his master and country. The

boy wept, and the impression never left him through his life.

He grew up to be a big fat man, with large eyes and broad shoulders very

characteristic of him. "Udo," the big-eyed, was the nickname they gave him. He

rejoiced in his muscular strength; wrestling was the favourite sport with him, and

he liked to roam in the mountains much of his time, a propensity which never left

him till the very end of his life. His attention was early called to the writings of

Wang Yang Ming, who of all Chinese philosophers, came nearest to that most

august faith, also of Asiatic origin, in his great doctrines of conscience and benign

but inexorable heavenly laws. Our hero's subsequent writings show this influence

to a very marked degree, all the Christianly sentiments therein contained testifying

to the majestic simplicity of the great Chinese, as well as to the greatness of the nature

that could take in all that, and weave out a character so practical as his. He also delved

a little into the Zen philosophy, a stoic form of Buddhism, "to kill my too keen sensibilities,"

as he told his friends afterward. So-called European culture he had absolutely none.

The broadest and most progressive of Japanese, his education was wholly Oriental.

But whence came the two dominant ideas of his life, which were (1) the united

empire, and (2) reduction of Eastern Asia? That Yang Ming philosophy, if logically

followed out, would lead to some such ideas is not difficult to surmise. So unlike

the conservative Chu philosophy fostered by the old governments for its own

preservation, it (Yang Ming philosophy) was progressive, prospective, and full of

promise. Its similarity to Christianity has been recognized more than once, and it

was practically interdicted in the country on that and other accounts. "This

resembles Yang-Ming-ism ; disintegration of the empire will begin with this." So

exclaimed Takasugi Shinsaku, a Choshu strategist of Revolutionary fame, when he

first examined the Christian Bible in Nagasaki. That something like Christianity

was a component force in the reconstruction of Japan is a singular fact in this part

of its history.

His situations and surroundings too must have helped him in forming his great

projects of life. Situated in the south-western corner of the country, Satzuma stood

nearest to the European influence, then coming all from that direction. Its

proximity to Nagasaki was a great advantage in this respect, and we are told of

foreign commerce actually carried on on some of its dependent islands, long before

formal permission was given thereto by the central government.

But of all outward influences, two living men had most to do with Saigo. One was

his own feudal master, Saihin of Satzuma, and the other was Fujita Toko of the

Mito han. That the former was no common character, no one can doubt.

Self-possessed and far-sighted, he early saw the inevitable changes that were

coming upon his country, and introduced reforms into his dominion to prepare for

the crises that were near at hand. It was he who fortified his own city of

Kagoshima, which cost so much for the English fleet to break down in 1863. It was

also he, who, notwithstanding his strong anti-foreign sentiments, received with

great respect Frenchmen who visited his shore, against the remonstrance of his

turbulent subjects to the contrary. "A pacific gentleman who avoided not war if

necessary," he was a man after Saigo's own heart, and the subject ceased not in

after years to express his dues to his great and farseeing master. The relation

between the two was that of two intimate friends, so near came they to each other

in their views as to the future of their country.

But the chief and greatest inspiration came from master spirit of the time. In

Fujita Toko of Mito,"the spirit of Yamato had concentrated itself." He was Japan

etherialized into a soul. Sharp in outlines and acutely angled, the farm was that of

the volcanic Fuji, with the soul in it of all sincerity. An intense lover of

righteousness, and an intense hater of the Western Barbarians, he drew around

him the rising generation; and Saigo, hearing of his fame at a distance, lost no

opportunity of seeing and feeling the man when he was in Yedo with his lord. No

two more congenial souls ever met together. "Only that young man shall carry to

posterity the plans that I now store in my bosom," said the master of the pupil.

"There is none to be feared under heaven except one, and that one is Master Toko,"

said the pupil of the master. The united empire, and the extension of its dominion

over the continent "so as to enable the land to stand on equal terms with Europe,"

and the practical ways of leading the nation thereto, seem to have taken final

shapes in Saigo's mind by the new influence he came under. He had now distinct

ideals to live up to, and his life since then was one direct march toward the mark

thus laid before him. The Revolution had its seed-thought sown in Toko's

vehement mind; but this needed transplanting to a less intense and more equable

soul like Saigo's, that it might bring forth an actual revolution. Toko died in the

earthquake of 1855 at the age of fifty, leaving his illustrious pupil to carry out the

ideals first conceived in his mind.

Shall we also deny to our hero a voice direct from Heaven's splendour, as he

roamed over his favourite mountains, oftentimes for days and nights in succession?

Did not a "still small voice" often tell him in the silence of cryptomeria forest, that

he was sent to this earth with a mission, the fulfillment of which was to be of great

consequence to his country and the world? Why did he mention Heaven so many

times in his writings and conversations if he had not such visitations? A slow,

silent, childlike man, he seems to have been mostly alone with his own heart,

where we believe he found One greater than himself and all the universe, holding

secret conversations with him. What cares he if the modern Pharisees call him a

heathen, and dispute as to the whereabouts of his soul in the future existence! "He

that follows the heavenly way abases not himself even though the whole world

speaks evil of him; neither thinks he himself sufficient even though they in unison

praise his name." "Deal with Heaven, and never with men. Do all things for

Heaven's sake. Blame not others; only search into the lack of sincerity in us." "The

law is of the universe and is natural. Hence he only can keep it who makes it his

aim to fear and serve Heaven. ........Heaven loves all men alike. So we must love

others with the love with which we love ourselves." Saigo said these things and

much else like them, and I believe he heard all these directly from Heaven.

III -HIS PART IN THE REVOLUTION

To write out in full Saigo's part in the Revolution would be to write the whole

history of the same. In one sense we may say, I think, that the Japanese

Revolution of 1868 was Saigo's revolution. Of course no one man can rebuild a

nation. We will not call New Japan Saigo's Japan. That certainly is doing great

injustice to many other great men who took part in this work. Indeed, in many

respects, Saigo had his superiors among his colleagues. As for matters of economic

rearrangement, Saigo was perhaps the least competent. He was not for the details

of internal administration as Kido and Okubo were, and Sanjo and Iwakura were

far his superiors in the work of the pacific settlement of the revolutionized country.

The New Empire as we have it now, would not have been, were it not for all these

men.

But we doubt whether the Revolution was possible without Saigo. A Kido or a

Sanjo we might not have had, and yet the Revolution we would have had, though

perhaps not so successfully. A need there was of a primal force that could give a

start to the whole movement, a soul that could give a shape to it, and drive it in the

direction ordered by Heaven's omnipotent laws. Once started and directed, the rest

was comparatively an easy work, much of it mere drudgeries, that could be done by

smaller men than he. And when we connect the name of Saigo so intimately with

the New Japanese Empire, it is because we believe him to be the starter and

director of a force generated in his big mind, and afterward applied to the course of

events then running in the society of his time.

Soon after his return from the Shogun's capital, after the all-important meeting

with Toko, Saigo identified himself with the anti-Tokugawa party then gaining

force in the western part of the country. His episode with Gessho, a learned

Buddhist priest and a warm advocate of the imperial cause, marks the point in his

career when his avowed aim began to be known to the public. Unable to shelter the

fugitive priest, with whose custody he was entrusted, from the hot pursuit of

Tokugawa men, Saigo proposed death to his guest and was accepted. They two

went to the sea on a moon-lit night, "drew maximum consolation from autumnal

view," and then hand in hand, the two patriots plunged into the sea. The splash

called the attention of the attendants then asleep, and search for the lost began at

once. Their bodies were secured, Saigo revived, but Gessho did not. The man who

had a new empire upon his shoulders thought not his life to be too precious to be

given away for his friend as a pledge of his affection and hospitality! It was this

weakness, - the weakness of "too keen sensibility" which he tried "to kill" by his

Zen Philosophy, - that brought upon his final destruction, as we shall see

afterward.

For this and other complicities in anti-Tokugawa movements, he was twice exiled

to south-sea islands. Returning to Kagoshima after its bombardment by the British

fleet in 1863, he at once resumed his old course, though this time more cautiously

than before. By his advice a pacific settlement was made between Choshu and the

Tokugawa Government; but a year later, when the latter forced unreasonable

demands upon the former, and their flat refusals called forth so-called Choshu

Invasion, Satzuma under Saigo's direction declined to send its quota of troops to

join the expedition. This policy of Satzuma was the beginning of the famous

coalition effected between it and Choshu, of so momentous import in the history of

the Revolution. The total discomfiture of the invading force, and the evident

imbecility of the old government in its dealings with foreign affairs, precipitated its

downfall much earlier than was expected; and on the same day when the coalition

secured an imperial decree for the upsetting of the tottering dynasty, the Shogun

out of his own free-will, laid down his authority of three centuries' standing, and

the rightful sovereigns was reinstated in power seemingly without any opposition.

(Nov. 14, 1867.) The occupation of the city of Kyoto by the army of the coalition and

its allies, "the Grand Proclamation of the Ninth Day of December," and the

evacuation of the Nijo castle by the Shogun followed in rapid succession. On the 3rd

of January 1868, the war began with the battle of Fushimi. The imperialists were

entirely successful, and the rebels, as the Tokugawa Party was called from that time,

retired toward the east. Two grand armies followed the latter, Saigo commanding

the Tokaido branch. No opposition was met, and on the 4th of April the castle of

Yedo was tendered to the imperialists. The Revolution considering its

tremendous after-effects was the cheapest ever bought.

And it was Saigo who bought it so cheaply and made it so effective, his real

greatness showing itself most conspicuously in these two contrary aspects of

our revolution. "The Grand Proclamation of the Ninth Day of December"

is comparable only to the similar proclamation of the Fourteenth of

July 1790 in the French capital, in its sweeping effect upon old institutions.

His self-possession was the stay of the imperialists when the first battle was

opened at Fushimi. A messenger came to him from the field and said, "Pray

send us a reenforcement. We are only one regiment, and the enemy's fire is hot

upon us." "I will," said General Saigo, "when every one of you is dead upon the field."

The messenger returned, and the enemy was repulsed. The side that had

such a general could not but win. This Tokaido army marched up to Shinagawa, and

the general was met by an old friend of his, Katzu by name, who alone among the

Tokugawa men saw its inevitable end, and would resign himself to

sacrifice the supremacy of his master's house that his

country might live thereby. "I believe my friend is at wit's end by this time," said

the commander of the imperial army to the messenger from the old government.

"Only by placing yourself in my position you can understand where I am," responds

the latter. The general bursts into a peal of laughter; he is amused at seeing

his friend in distress ! His mind is now inclined toward peace. He goes back to Kyoto,

and maintains against all oppositions amnesty toward the Shogun and his

followers, and returns to Yedo with terms very favorable to the beleagured party. It

is said that a few days before he finally made up his mind for peace, Katzu took him

up to the Atago Hill for a friendly walk. Seeing "the city of magnificent dimensions"

under his feet, the general's heart was deeply touched. He turned to his friend and said,

"In case we exchange arms, I believe these innocent peoples will have to suffer on

our account," and was silent for some moment. His "sensibility" moved in him;

he must have peace for those innocent ones' sake. "The strong man is most

powerful when unimpeded by the weak." Saigo's strength had considerable

of womanly pity in it. The city was spared, peace was concluded, and the

Shogun was made to lay down his arms and tender his castle to the Emperor.

The Emperor reinstated in his rightful position, the country united under its

rightful sovereign, and the government set moving in the direction he had

aimed at, Saigo retired at once to his home in Satzuma, and there for several years occupied

himself mostly in drilling a few battalions of soldiers. To him the war did not end,

as it did to others of his countrymen. Great social reforms that were also yet to be

introduced into the country needed force, as that other purpose for which in his eye

the united empire was only a step. Called up to the capital, he filled the

all-important office of Sangi (Chief Councillor) with other men of revolutionary

fame. But time came when his associates could follow him no longer. Hitherto they

had come together because they had an aim in common; but where they wanted to

stop, he wanted to begin, and rupture came at last.

IV-THE COREAN AFFAIR

Saigo was too much of a moralist to go to war merely for conquest's sake. His

object of the reduction of Eastern Asia came necessarily out of his views of the then

state of the world. That Japan might be a compeer with the Great Powers of

Europe, she needed a considerable extension of her territorial possessions, and

enough aggressiveness to keep up the spirit of her people. Then too, we believe he

had somehow an idea of the great mission of his country as the leader of Eastern

Asia. To crush the weak was never in him; but to lead them against the strong and

so crush the proud, was his whole soul and endeavour. The single fact that his

ideal hero was said to be George Washington, and that he showed intense dislike

toward Napoleon and men of his type, should be enough evidence that Saigo was

never a slave of low ambitions.

Yet with all his high notions of his country's mission, he would not go to war

without sufficient cause for it. To do so would be against Heaven's law that he

made so much of. But when an opportunity presented itself without his own

making, it was very natural that he took it as a heaven-sent one for his country to

enter upon a career assigned her from the beginning of the world. Corea, her

nearest continental neighbor, proved herself insolent to several of the Japanese

envoys sent out by the new government. Moreover, she showed distinct enmity

against the Japanese residents there, and made a public proclamation to her

people highly derogatory to the dignity of her friendly neighbor. Should such go

unheeded? argued Saigo and men of his inclination. The insolence was not yet

sufficient to precipitate war. But let an embassy consisting of a few men of the

highest rank be sent to the Peninsular Court to demand justice for her insolence;

and should she still insist in her haughty attitude, and add insult, and very

possibly, personal injury, to the new embassy, let that be the signal to the nation to

dispatch its troops into the continent, and extend its conquest as far as Heaven

would permit. And since great responsibility and utmost danger would attend such

an embassy, he (Saigo) himself would like to be appointed to that office. The

conqueror will first lay down his life to open a way of conquest to his countrymen!

Never in History was conquest undertaken in this fashion.

The slow, silent Saigo was all fire and activity when the question of the Corean

embassy was discussed in the cabinet. He implored his colleagues to appoint him

as the chief envoy, and when it was fairly settled that his request would be granted,

his gladness was that of a child leaping for joy possessed with the object of its

heart's desire. Here is a letter which he wrote to his friend Itagaki (now count) by

whose special endeavour the appointment was privily settled in the court.

"Itagaki Sama,

I called upon you yesterday, but you were absent, and I was sent back without

expressing my thanks to you. By your effort I am to have all I wished. My illness is

all gone now. Transported with gladness, I new through the air from Minister

Sanjo's to your mansion; my feet were so light. No mire fear of 'side thrust' I

suppose. Now that my aim is secured, I may retire to my residence in Aoyama and

wait for the happy issue. This is only to convey my gratitude to you.

Saigo."

At this juncture, Iwakura returned with Okubo and Kido from their tour around

the world. They saw civilization in its centre, its comfort and happiness. They no

more thought of foreign war than Saigo did of Parisian or Viennese ways of living.

So, resorting themselves to duplicities and ambiguities of all kinds, they in concert

did all in their power to overthrow the decision reached in the cabinet council

during their absence, and taking advantages of Minister Sanjo's illness, they

succeeded at last in carrying their ways through. The Corean Embassy Act was

repealed, Nov. 28, l873. Saigo, who to all outward appearances had known no

anger thus far, was now wild over the measures of the "long-sleeved," as he called

the coward courtiers. That the act was repealed was not what offended him most;

but the way in which it was rescinded, and the motives that led thereto, were

objectionable to him beyond his power of forbearance. He made up his mind that he

would do nothing with the rotten government, threw his written resignation upon

the cabinet-table, gave up his residence in Tokio, and retired at once to his home in

Satzuma, never again to join the government that was set up mostly through his

endeavour.

With the suppression of the Corean Affair ceased all the aggressive measures of

the government, and its whole policies since they have been directed toward what

its supporters called "internal development." And agreeably to the heart's wish of

Iwakura and his "peace-party," the country has had much of what they called

civilization. Yet withal also came much effeminacy, fear of decisive actions, love

of peace at the cost of plain justice, and much else that the true samurai laments.

"What is civilization but an effectual working of righteousness, and not

magnificence of houses, beauty of dresses, and ornamentation of outward

appearance." This was Saigo's definition of civilization, and we are afraid

civilization in his sense has not made much progress since his time.

V-SAIGO AS A REBEL

We need say but very little about this last and most lamentable part of Saigo's life.

That he turned a rebel against the government of his time was a fact. What motive

led him to take that position has been conjectured in many ways. That his old

weakness, "too keen sensibility," was the main cause of his uniting with the rebels

seems quite plausible. Some five thousand young men who worshipped him as the

only man in the world, went into an open rebellion against the government,

seemingly without his knowledge, and much against his will. Their success

depended wholly upon his lending his name and influence to their cause. A

strongest of men, he was almost helpless before the suppliant entreaty of the needy.

Twenty years ago he had promised his life to his guest as a pledge of his

hospitality; and now again he might have been induced to sacrifice his life, his

honour, his all, as a pledge of his friendship to his admiring pupils. This view of

things is taken by many who knew him best.

That he was strongly disaffected with the government of his time needs no

controversy; but that he a level-headed man should go to war for the mere sake of

enmity is hard to conjecture. Are we mistaken when we maintain, that in his case

at least, the rebellion was a result of disappointment in the grand aims of his life?

Though not directly caused by him, it found him in unspeakable anguish of soul,

because the revolution of 1868 produced the result so contrary to his ideal. Should

the rebellion chance to be a success, might he not realize yet the great dreams of

his life? Doubtingly, yet not entirely without some hope, he united with the rebels

and shared with them the fate he seemed to have instinctively foreseen. But

history may wait a hundred years more before it can settle this part of his life.

He remained a passive figure all through the war, Kirino and others looking

after all the manoeuvers in the field. They fought from February to September,

1877, and when their hopes were all shattered, they forced their way back to

Kagoshima, there to be buried in their "fathers' grave-yard." There beleaguered in

the Castle Hill, all the government forces gathered at its foot, our hero was playing

go in the best of spirit. Turning to one of his attendants he said, "Aren't you the one

the latchet of whose wooden shoes I mended one day, as I was returning from my

farm, drawing my packhorse behind me?" The man remembered the occasion,

confessed his insolence, and sincerely asked for forgiveness. "Nothing!" replied

Saigo, "Too much leisure made me to poke you a little." The fact was, the General

did yield once to the impudent demands of two youths, who, as was the custom in

Satzuma, used the right of the samurai to have his wooden-shoes mended by any

farmer he happened to meet. The farmer in this case happened to be the great

Saigo, who without a word of complaint, did the menial service, and went away in

all humility. We are exceedingly thankful for this piece of reminiscence given of

him by the very man who attended upon him in his last hours. Saint Aquinas was

not more humble than this our Saigo.

On the morning of 24th of September l877, general assault was made upon the

Castle Hill by the government force. Saigo was on the point of rising with his

comrades to meet the enemy, when a bullet struck his hip. Soon the little party

was annihilated, and Saigo's remains fell into his enemy's hand. "See that no

rudeness is done to them," cried one of the enemy's generals. "What a mildness in

his countenance!" said another. They that killed him were all in mourning. In tears

they buried him, and with tears his tomb is visited by all to this day. So passed

away the greatest, and we are afraid, the last of the samurai.

VI-HIS WAYS OF LIVING AND VIEWS OF LIFE

History has yet to wait for the just estimate of Saigo's public service to his

country; but it has enough materials at its command for forming right views of the

kind of man he really was. And if the latter aspect of his life will help much to clear

up the former, I believe my readers will pardon me for dwelling at some length

upon his private life and opinions.

First of all, we know of no man who had fewer wants in life than he. The

commander-in-chief of the Japanese army, the generalissimo of the Imperial

Bodyguard, and the most influential of the cabinet-members, his outward

appearance was that of the commonest soldier. When his monthly income was

several hundred yen, he had enough for his wants with fifteen, and every one of his

needy friends was welcome to the rest. His residence in Bancho, Tokio, was a

shabby-looking structure the rent three yen a month. His usual costume was

Satzuma-spun cotton stuff, girdled with a broad calico obi, and large wooden clogs

on his feet. In this attire he was ready to appear at any place, at the Imperial

dinner-table, as anywhere else. For food he would take whatsoever was placed

before him. Once a visitor found him in his residence, he and several of his soldiers

and attendants surrounding a large wooden bowl, and helping themselves to

buck-wheat macaroni cooled in the receptacle. That seemed to be his favorite

banquet, eating with young fellows, himself a big child of the simplest nature.

Careless about his body, he was also careless about his possessions. He gave up a

fine lot of land in his possession in the most prosperous section of the city of Tokio

to a national bank just then started, and when asked its price, he refused to

mention it; and so it remains to this day in the possession of the said corporation,

worth several hundred thousand dollars. A large income from his pension was

spent wholly for the support of a school which he started in Kagoshima. One of his

Chinese poems reads,

"Does the world know our family law?

We leave not substance to our children."

And so he left nothing to his widow and children; but the nation took care of them,

though he died a rebel. Modern Economic Science may have much to say against

this "carelessness" of his.

He had one hobby, and that was the dog-kind. Though he accepted nothing else

that was taken as a present to him, anything that related to dogs he received with

all thankfulness. Chromos, lithographs, pencil-sketches of the canine tribe were

always very pleasing to him. It is said that when he gave up his house in Tokio, he

had a large boxful of pictures of dogs. One of his letters to General Oyama was very

particular about collars for his hounds "Many thanks for the specimens of the

dog-collars you kindly sent me," he writes. "I think they are superior to imported

articles. Only if you could make them three inches longer, they would fit my

purpose exactly. Make four or five of them, I beseech you. And once more, a little

broader and five inches longer, I pray, etc." His dogs were his friends all through

his life. He often spent days and nights with them in the mountains. The loneliest

of man, he had dumb brutes to share his loneliness.

He disliked disputings, and he avoided them by all possible means. Once he was

invited to an Imperial feast, at which he appeared in his usual plain costume. As

he retired, he missed his clogs left at the palace-entrance, and as he would not

trouble anybody about them, he walked out barefooted; and that in a drizzling rain.

When he came to the castle-gate, the sentinel called him to halt, and demanded of

him an explanation of his person, - a doubtful figure he appeared in his commonest

garb. "General Saigo," he replied. But they believed not his words, and allowed him

not to pass the gate. So he stood there in the rain waiting for somebody who might

identify him to the sentinel. Soon a carriage approached with Minister Iwakura in

it. The barefooted man was proved to be the general, was taken into the minister's

coach, and so carried away. - He had a servant, Kuma by name, a well-known

figure in his modest household for many years. The latter, however, once

committed an offence grave enough to have his position forfeited. But the

indulgent master was solicitous about his servant's future if discharged from his

service. So he simply kept him in his house; but for many years he gave him not a

single order to be executed. Kuma survived his master many years, and was one of

the deepest mourner for the ill-fated hero.

A witness has this to say of Saigo's private life: "I lived with him thirteen years;

and never have I seen him scolding his servants. He himself looked to the making

and unmaking of his bed, to the opening and shutting of his room-windows, and to

most other things that pertained to his person. But in cases others were doing

them for him, he never interfered; neither did he decline help when offered. His

carelessness and entire artlessness were those of a child."

Indeed he was so loathe to disturb the peace of others that he often made visits

upon their houses, but dared not to call for notice from inside; but stood in the

entrance thereof and there waited till somebody happened to come out and find

him!

Such was his living; so lowly and so simple; but his thinking was that of a saint

and a philosopher, as we have had already some occasions to show.

"Revere Heaven; love people," summed up all his views of life. All wisdom was

there; and all un-wisdom, in love of self. What conceptions he had of Heaven;

whether he took it to be a Force or a Person, and how he worshiped it except in his

own practical way, we have no means of ascertaining. But that he knew it to be

all-powerful, unchangeable, and very merciful, and its Laws to be all-binding

unassailable, and very beneficent, his words and actions abundantly testify. We

have already given some of his expressions about Heaven and its Laws. His

writings are full of them, and we need not multiply them here. When he said,

"Heaven loveth all men alike; so we must love others with the love with which we

love ourselves," he said all that is in the Law and Prophets, and some of us may be

desirous to inquire whence he got that grand doctrine of his.

And this Heaven was to be approached with all sincerity; else the knowledge of its

ways was unattainable. Human wisdoms he detested ; but all wisdoms were to

come from the sincerity of one's heart and purpose. Heart pure and motive high,

ways are at hand as we need them, in the council-hall as on the battle-field. He

that schemes always is he that has no schemes when crises are at hand. In his own

words, "Sincerity's own realm is one's secret chamber. Strong there, a man is strong

everywhere." Insincerity, and its great child, Selfishness, are the prime causes of

our failures in life. Saigo says, "A man succeeds by overcoming himself, and fails by

loving himself. Why is it that many have succeeded in eight and failed

in the remaining two? Because when success attended them, love of self grew in them;

and vigilance departing, and desire for ease returning, their work became onerous

to them, and they failed." Hence we are to meet all the emergencies of life with

our lives in our hands. "I have my life to offer," he often uttered when he had

some action to propose in his responsible position. That entire self-abnegation was

the secret of his courage is evident from the following remarkable utterance of his:

"A man that seeks neither life, nor name, nor rank, nor money, is the hardest man

to manage. But with only such life's tribulations can be shared, and such only can

bring great things to his country."

A believer in Heaven, its laws and its time, he was also a believer in himself, as

one kind of faith always implies the other kind. "Be determined and do," he said,

"and even gods will flee from before you." Again he said: "Of opportunities there

are two kinds : those that come without our seeking and those that are of our own

make. What the world calls opportunity is usually the former kind. But the true

opportunity comes by acting in accordance with reason, in compliance with the

need of the time. When crises are at hand, opportunities must be caused by us." A

MAN, therefore, a capable man, he pried above all things. "Whatever be the ways

and institutions we speak about," were his words, "they are impotent unless there

are men to work them. Man first; then the working of means. Man is the first

treasure, and let every one of us try to be a man."

A "reverer of Heaven" cannot but be a reverer and observer of righteousness.

"An effectual working of righteousness" was his definition of civilization. To him

there was nothing under heaven so precious as righteousness. His life, of course,

and his country even, were not more precious than righteousness. He says: "Unless

there is a spirit in us to walk in the ways of righteousness, and fall with the

country if for righteousness' sake, no satisfactory relation with foreign powers can

be expected. Afraid of their greatness and hankering after peace, and abjectly

following their wishes, we soon invite their contemptuous estimate of ourselves.

Friendly relations will thus begin to cease, and we shall be made to serve them at

last." In a similar strain he says: "When a nation's honour is in any way injured,

the plain duty of its government is to follow the ways of justice and righteousness

even though the nation's existence is jeopardized thereby. * * * * * A government

that trembles at the word 'war,' and only makes it a business to buy slothful peace,

should be called a commercial regulator, and it should not be called a government."

And the man who uttered these words was the object of universal esteem by all the

ambassadors of the foreign courts then represented in our capital. None esteemed

him more than Sir Harry Parkes of her Britannic Majesty's Legation, who as an

adept in the art of Oriental diplomacy, was for a long time a shrewd upholder of

the British interests on our shores. "Be just and fear not" was Saigo's method of

running a government.

With such a singleness of view, he was naturally very clear-sighted as to the

outcome of the movements then going on around him. Long before the Revolution,

when the new government was yet a day-dream even to many of its advocates, it

was an accomplished reality to Saigo. It is said that, when, after many years of

banishment, he was sent to in his isle of exile to call him back to his old position of

responsibility, he told the messenger, with diagrams on the beach-sand, all the

manoeuvres he had framed in his mind for the upbuilding of the new empire; and

so true to the situation was the prescience then offered that the listener told his

friends afterwards, that in his view, Saigo was not a man but a god. And we have

seen his perfect self-possession during the Revolution, - a natural result of his clear

vision. When it had fairly begun, there was much anxiety in some quarters as to

the position of the Emperor in the new government, seeing that for well-nigh ten

centuries his real situation had been a very undefinable one. Mr. Fukuba, a

well-known court-poet, asked Saigo on this wise:

"The Revolution I desire to have; but when the new government is set up, where

shall we place our holy Emperor?"

To which Saigo's very explicit reply was as follows:

"In the new government we shall place the Emperor where he should be; that is

make him personally see to the affairs of the state, and so fulfill his

heaven-appointed mission."

No tortuosities in this man. Short, straight, clear as sunlight, as the ways of

righteousness always are.

Saigo left us no books. But he left us many poems, and several essays. Through

these occasional effusions of his, we catch glimpses of his internal state, and we

find it to be the same as was reflected in all his actions. Pedantry there is not in all

his writings. Unlike many Japanese scholars of his degree of attainment, his words

and similes are the simplest that can be imagined. For instance, can anything be

simpler than this:

"Hair I have of thousand strings,

Darker than the lac.

A heart I have an inch long,

Whiter than the snow.

My hair may divided be,

My heart shall never be."

Or this, very characteristic of him:

"Only one way, 'Yea and Nay;'

Heart ever of steel and iron.

Poverty makes great men;

Deeds are born in distress.

Through snow, plums are white,

Through frosts, maples are red;

If but Heaven's will be known,

Who shall seek slothful ease!"

The following bit of a mountain-song of his is perfectly natural to him:

"Land high, recesses deep,

Quietness is that of night.

I hear not human voice,

But look only at the skies."

We have space here only for a part of his essay entitled, "On the Production of

Wealth."

"In the book of 'Sa-den' it is written: 'Virtue is a source of which wealth is an

outcome.' Virtue prospers, and wealth comes by itself. Virtue declines, and in the

same proportion wealth diminishes. For wealth is by replenishing the land and

giving peace to the people. The small man aims at profiting himself; the great man,

at profiting the people. One is selfishness, and it decays. The other is

public-spiritedness, and it prospers. According as you use your substance, you have

prosperity or decay, abundance or poverty, rise or fall, life or death. Should we not

be on our guard therefore?

"The world says: 'Take and you shall have wealth, and give and you shall lose it.'

Oh what an error! I seek a comparison in agriculture. The covetous farmer sparing

of his seeds sows but niggardly; and then sits and waits for the harvest of autumn.

The only thing he shall have is starvation. The good farmer sows good seeds, and

gives all his cares thereto. The grains multiply hundredfold, and he shall have

more than he can dispose of. He that is intent upon gathering knows only of

harvesting, and not of planting. But the wise man is diligent in planting; therefore

the harvest comes without his seeking.

* * * * *

"To him who is diligent in virtue, wealth comes without his seeking it. Hence what

the' world calls loss is not loss, and what it calls gain is not gain. The wise man of

old thought it as gain to bless and give to the people, and loss to take from them.

Quite otherwise at present.

* * * * *

"Ah, can it be called wisdom to walk contrary to the ways of the sages, and yet

seek wealth and abundance for the people? Should it not be called unwisdom to

walk contrary to the law (true) of gain and loss, and yet devise means to enrich the

land? The wise man economizes to give in charity. His own distress troubles him

not; only that of his people does. Hence wealth flows to him as water gushes from

the spring. Blessings are rained down, and the people bathe in them. All this comes,

because he knows the right relation of wealth to virtue, and seeks the source, and

not the outcome."

"An old-school economy," I hear our modern Benthamites say. But it was the

economy of Solomon, and of One greater than Solomon, and it can never be old so

long as the universe stands as it did all these centuries. "There is that scattereth,

and yet increaseth; and there is that withholdeth more than is meet, but it tendeth

to poverty." "Seek ye first the kingdom of God and its righteousness; and all these

things shall be added unto you." Is not Saigo's essay a fit commentary on these

divine words?

If I am to mention the two greatest names in our history, I

unhesitatingly name Taiko and Saigo. Both had continental ambitions, and the

whole world as their field of action. Incomprehensively great above all their

countrymen both of them were, but of two entirely different kinds of greatness.

Taiko's greatness, I imagine, was somewhat Napoleonic. In him there was much of

the charlatan element so conspicuous in his European representative, though I am

sure in very much smaller proportion. His was the greatness of genius, of inborn

capacity of mind, great without attempting to be great. But not so Saigo's. His was

Cromwellian, and only for the lack of Puritanism, he was not a Puritan, I think.

Sheer will-power had very much to do in his case, - the greatness of moral kind, the

best kind of greatness. He tried to rebuild his nation upon a sound moral basis, in

which work he partially succeeded.

参考文献

|

TOP

|

出典: 百科事典

| 西郷 隆盛 |

|

|

西郷 隆盛(さいごう たかもり、旧字体: 西鄕隆盛、文政10年12月7日(1828年1月23日) - 明治10年(1877年)9月24日)は、日本の武士(薩摩藩士)、軍人、政治家。薩摩藩の盟友、大久保利通や長州藩の木戸孝允(桂小五郎)と並び、「維新の三傑」と称される。維新の十傑の1人でもある。

略歴

薩摩国薩摩藩の下級藩士・西郷吉兵衛隆盛の長男。名(諱)は元服時には隆永(たかなが)、のちに武雄、隆盛(たかもり)と改めた。幼名は小吉、通称は吉之介、善兵衛、吉兵衛、吉之助と順次変えた。号は南洲(なんしゅう)。隆盛は父と同名であるが、これは王政復古の章典で位階を授けられる際に親友の吉井友実が誤って父・吉兵衛の名を届けたため、それ以後は父の名を名乗ったためである。一時、西郷三助・菊池源吾・大島三右衛門、大島吉之助などの変名も名乗った。

西郷家の初代は熊本から鹿児島に移り、鹿児島へ来てからの7代目が父・吉兵衛隆盛、8代目が吉之助隆盛である。次弟は戊辰戦争(北越戦争・新潟県長岡市)で戦死した西郷吉二郎(隆廣)、三弟は明治政府の重鎮西郷従道(通称は信吾、号は竜庵)、四弟は西南戦争で戦死した西郷小兵衛(隆雄、隆武)。大山巌(弥助)は従弟、川村純義(与十郎)も親戚である。

薩摩藩の下級武士であったが、藩主の島津斉彬の目にとまり抜擢され、当代一の開明派大名であった斉彬の身近にあって、強い影響を受けた。斉彬の急死で失脚し、奄美大島に流される。その後復帰するが、新藩主島津忠義の実父で事実上の最高権力者の島津久光と折り合わず、再び沖永良部島に流罪に遭う。しかし、家老・小松清廉(帯刀)や大久保の後押しで復帰し、元治元年(1864年)の禁門の変以降に活躍し、薩長同盟の成立や王政復古に成功し、戊辰戦争を巧みに主導した。江戸総攻撃を前に勝海舟らとの降伏交渉に当たり、幕府側の降伏条件を受け入れて、総攻撃を中止した(江戸無血開城)。

その後、薩摩へ帰郷したが、明治4年(1871年)に参議として新政府に復職。さらにその後には陸軍大将・近衛都督を兼務し、大久保、木戸ら岩倉使節団の外遊中には留守政府を主導した。朝鮮との国交回復問題では朝鮮開国を勧める遣韓使節として自らが朝鮮に赴くことを提案し、一旦大使に任命されたが、帰国した大久保らと対立する。明治6年(1873年)の政変で江藤新平、板垣退助らとともに下野、再び鹿児島に戻り、私学校で教育に専念する。佐賀の乱、神風連の乱、秋月の乱、萩の乱など士族の反乱が続く中で、明治10年(1877年)に私学校生徒の暴動から起こった西南戦争の指導者となるが、敗れて城山で自刃した。

死後十数年を経て名誉を回復され、位階は正三位。功により、継嗣の寅太郎に侯爵を賜る。

生涯

本項で、年月日は明治5年12月2日までは旧暦(太陰太陽暦)である天保暦、明治6年1月1日以後は新暦(太陽暦)であるグレゴリオ暦を用い、和暦を先に、その後ろの( )内にグレゴリオ暦を書く。

幼少・青年時代

文政10年12月7日(1828年1月23日)、薩摩国鹿児島城下加治屋町山之口馬場(下加治屋町方限)で、御勘定方小頭の西郷九郎隆盛(のち吉兵衛隆盛に改名、禄47石余)の第1子として生まれる。西郷家の家格は御小姓与であり、下から2番目の身分である下級藩士であった。本姓は藤原氏(系譜参照)を称するが明確ではない。先祖は肥後国の菊池家の家臣で、江戸時代の元禄年間に島津家々臣になる。

天保10年(1839年)、郷中(ごじゅう)仲間と月例のお宮参りに行った際、他の郷中と友人とが喧嘩しその仲裁に入るが、上組の郷中が抜いた刀が西郷の右腕内側の神経を切ってしまう。西郷は三日間高熱に浮かされたものの一命は取り留めたが、刀を握れなくなったため武術を諦め、学問で身を立てようと志した。天保12年(1841年)、元服し吉之介隆永と名乗る。この頃に下加治屋町(したかじやまち)郷中の二才組(にせこ)に昇進する。

郡方書役時代

弘化元年(1844年)、郡奉行・迫田利済配下となり、郡方書役助をつとめ、御小姓与(一番組小与八番)に編入された。弘化4年(1847年)、郷中の二才頭となった。嘉永3年(1850年)、高崎崩れ(お由羅騒動)で赤山靭負(ゆきえ)が切腹し、赤山の御用人をしていた父から切腹の様子を聞き、血衣を見せられた。これ以後、世子・島津斉彬の襲封を願うようになった。

伊藤茂右衛門に陽明学、福昌寺(島津家の菩提寺)の無参和尚に禅を学ぶ。この年、赤山らの遺志を継ぐために、近思録崩れの秩父季保愛読の『近思録』を輪読する会を大久保正助(利通)・税所喜三左衛門(篤)・吉井幸輔(友実)・伊地知竜右衛門(正治)・有村俊斎(海江田信義)らとつくった(このメンバーが精忠組のもとになった)。

斉彬時代

嘉永4年(1851年)2月2日、島津斉興が隠居し、島津斉彬が薩摩藩主になった。嘉永5年(1852年)、父母の勧めで伊集院兼寛の姉・須賀(敏(敏子)であったとも云われる)と結婚したが、7月に祖父・遊山、9月に父・吉兵衛、11月に母・マサが相次いで死去し、一人で一家を支えなければならなくなった。嘉永6年(1853年)2月、家督相続を許可されたが、役は郡方書役助と変わらず、禄は減少して41石余であった。この頃に通称を吉之介から善兵衛に改めた。12月、ペリーが浦賀に来航し、攘夷問題が起き始めた。

安政元年(1854年)、上書が認められ、斉彬の江戸参勤に際し、中御小姓・定御供・江戸詰に任ぜられ、江戸に赴いた。4月、「御庭方役」となり、当代一の開明派大名であった斉彬から直接教えを受けるようになり、またぜひ会いたいと思っていた碩学・藤田東湖にも会い、国事について教えを受けた。鹿児島では11月に、貧窮の苦労を見かねた妻の実家、伊集院家が西郷家から須賀を引き取ってしまい、以後、二弟の吉二郎が一家の面倒を見ることになった。

安政2年(1855年)、西郷家の家督を継ぎ、善兵衛から吉兵衛へ改める(8代目吉兵衛)。12月、越前藩士・橋本左内が来訪し、国事を話し合い、その博識に驚く。この頃から政治活動資金を時々、斉彬の命で賜るようになる。安政3年(1856年)5月、武田耕雲斎と会う。7月、斉彬の密書を水戸藩の徳川斉昭に持って行く。12月、第13代将軍・徳川家定と斉彬の養女・篤姫(敬子)が結婚。この頃の斉彬の考え方は、篤姫を通じて一橋家の徳川慶喜を第14代将軍にし、賢侯の協力と公武親和によって幕府を中心とした中央集権体制を作り、開国して富国強兵をはかって露英仏など諸外国に対処しようとするもので、日中韓同盟をも視野にいれた壮大な計画であり、西郷はその手足となって活動した。

安政4年(1857年)4月、参勤交代の帰途に肥後熊本藩の長岡監物・津田山三郎と会い、国事を話し合った。5月、帰藩。次弟・吉二郎が御勘定所書役、三弟・信吾が表茶坊主に任ぜられた。10月、徒目付・鳥預の兼務を命ぜられた(大久保利正助も共に徒目付になった)。11月、藍玉の高値に困っていた下関の白石正一郎に薩摩の藍玉購入の斡旋をし、以後、白石宅は薩摩人の活動拠点の一つになった。12月、江戸に着き、将軍継嗣に関する斉彬の密書を越前藩主・松平慶永(春嶽)に持って行き、この月内、橋本左内らと一橋慶喜擁立について協議を重ねた。安政5年(1858年)1、2月、橋本左内・梅田雲浜らと書簡を交わし、中根雪江が来訪するなど情報交換し、3月には篤姫から近衛忠煕への書簡を携えて京都に赴き、僧・月照らの協力で慶喜継嗣のための内勅降下をはかったが失敗した。

5月、彦根藩主・井伊直弼が大老となった。直弼は、6月に日米修好通商条約に調印し、次いで紀州藩主・徳川慶福(家茂)を将軍継嗣に決定した。7月には不時登城を理由に徳川斉昭に謹慎、松平慶永に謹慎・隠居、徳川慶喜に登城禁止を命じ、まず一橋派への弾圧から強権を振るい始めた(広義の安政の大獄開始)。この間、西郷は6月に鹿児島へ帰り、松平慶永からの江戸・京都情勢を記した書簡を斉彬にもたらし、すぐに上京し、梁川星巌・春日潜庵らと情報交換した。7月8日、斉彬は鹿児島城下天保山で薩軍の大軍事調練を実施した(兵を率いて東上するつもりであったともいわれる)が、7月16日、急逝した。7月19日、斉彬の弟・島津久光の子・忠義が家督相続し、久光が後見人となったが、藩の実権は斉彬の父・斉興が握った。

大島潜居前後

安政5年(1858年)7月27日、京都で斉彬の訃報を聞き、殉死しようとしたが、月照らに説得されて、斉彬の遺志を継ぐことを決意した。8月、近衛家から託された孝明天皇の内勅を水戸藩・尾張藩に渡すため江戸に赴いたが、できずに京都へ帰った。以後9月中旬頃まで諸藩の有志および有馬新七・有村俊斎・伊地知正治らと大老・井伊直弼を排斥し、それによって幕政の改革をしようとはかった。しかし、9月9日に梅田雲浜が捕縛され、尊攘派に危機が迫ったので、近衛家から保護を依頼された月照を伴って伏見へ脱出し、伏見からは有村俊斎らに月照を託し、大坂を経て鹿児島へ送らせた。

9月16日、再び上京して諸志士らと挙兵をはかったが、捕吏の追及が厳しいため、9月24日に大坂を出航し、下関経由で10月6日に鹿児島へ帰った。捕吏の目を誤魔化すために藩命で西郷三助と改名させられた。11月、平野国臣に伴われて月照が鹿児島に来たが、幕府の追及を恐れた藩当局は月照らを東目(日向国)へ追放すること(これは道中での切り捨てを意味していた)に決定した。月照・平野らとともに乗船したが、前途を悲観して、16日夜半、竜ヶ水沖で月照とともに入水した。すぐに平野らが救助したが、月照は死亡し、西郷は運良く蘇生し同志の税所喜三左衛門がその看病にあたったが、回復に一ヶ月近くかかった。藩当局は死んだものとして扱い、幕府の捕吏に西郷と月照の墓を見せたので、捕吏は月照の下僕・重助を連れて引き上げた。

12月、藩当局は、幕府の目から隠すために西郷の職を免じ、奄美大島に潜居させることにした。12月末日、菊池源吾[注 2]と変名して、鹿児島から山川郷へ出航した。安政6年(1859年)1月4日、伊地知正治・大久保利通・堀仲左衛門(次郎)等に後事を託して山川港を出航し、七島灘を乗り切り、名瀬を経て、1月12日に潜居地の奄美大島龍郷村阿丹崎に着いた。

島では美玉新行の空家を借り、自炊した。間もなく重野安繹の慰問を受け、以後、大久保利通・税所篤・吉井友実・有村俊斎・堀仲左衛門らからの書簡や慰問品が何度も送られ、西郷も返書を出して情報入手につとめた。この間、11月、龍家の一族、佐栄志の娘・とま(のち愛加那と改める)を島妻とした。当初、扶持米は6石であったが、万延元年には12石に加増された。また留守家族にも家計補助のために藩主から下賜金が与えられた。来島当初は流人としての扱いを受け、孤独に苦しんだ。しかし、島の子供3人の教育を依頼され、間切横目・藤長から親切を受け、島妻を娶るにつれ、徐々に島での生活になじみ、万延元年(1860年)11月2日には菊次郎が誕生した。文久元年(1861年)9月、三弟の竜庵が表茶坊主から還俗して信吾と名乗った。11月、見聞役・木場伝内(木場清生)と知り合った(のち木場は大坂留守居役・京都留守居役となり西郷を助けた)。

寺田屋騒動前後

文久元年(1861年)10月、久光は公武周旋に乗り出す決意をして要路重臣の更迭を行ったが、京都での手づるがなく、小納戸役の大久保・堀次郎らの進言で西郷に召還状を出した。西郷は11月21日に召還状を受け取ると、世話になった人々への挨拶を済ませ、愛加那の生活が立つようにしたのち、文久2年(1862年)1月14日に阿丹崎を出帆し、口永良部島・枕崎を経て2月12日に鹿児島へ着いた。2月15日、生きていることが幕府に発覚しないように西郷三助から大島三右衛門[注 3]と改名した。同日、久光に召されたが、久光が無官で、斉彬ほどの人望が無いことを理由に上京すべきでないと主張し、また、「御前ニハ恐レナガラ地ゴロ(地ゴロは田舎者という意味)」なので周旋は無理だと言ったので、久光の不興を買った。一旦は同行を断ったが、大久保の説得で上京を承諾し、旧役に復した。3月13日、下関で待機する命を受けて、村田新八を伴って先発した。

下関の白石正一郎宅で平野国臣から京大坂の緊迫した情勢を聞いた西郷は、3月22日、村田新八・森山新蔵を伴い大坂へ向けて出航し、29日に伏見に着き、激派志士たちの京都焼き討ち・挙兵の企てを止めようと試みた。しかし、4月6日、姫路に着いた久光は、西郷が待機命令を破ったこと、堀次郎・海江田信義から西郷が志士を煽動していると報告を受けたことから激怒し、西郷・村田・森山の捕縛命令を出した。捕縛された西郷らは10日、鹿児島へ向けて船で護送された。

一方、浪士鎮撫の朝旨を受けた久光は、伏見の寺田屋に集結している真木保臣(和泉)・有馬新七らの激派志士を鎮撫するため、4月23日に奈良原繁・大山格之助(大山綱良)らを寺田屋に派遣した。奈良原らは激派を説得したが聞かれず、やむなく有馬新七ら8名を上意討ちにした(寺田屋騒動)。この時に挙兵を企て、寺田屋、その他に分宿していた激派の中には三弟の信吾、従弟の大山巌(弥助)の外に篠原国幹・永山弥一郎なども含まれていた。護送され山川港で待命中の6月6日、西郷は大島吉之助に改名させられ、徳之島へ遠島、村田新八は喜界島(村田新八『宇留満乃日記』参照)へ遠島が命ぜられた。未処分の森山新蔵は船中で自刃した。

徳之島・沖永良部島遠流

文久2年(1862年)6月11日、西郷は山川を出帆し、村田も遅れて出帆したが、向かい風で風待ちのために屋久島一湊で出会い、7、8日程風待ちをし、ともに一湊を出航、奄美へ向かった。七島灘で漂流し、奄美を経て(以上は「宇留満乃日記」に詳しい)、やっと7月2日に西郷は徳之島湾仁屋に到着した。偶然にも、この渡海中の7月2日に愛加那が菊草(菊子)を生んだ。

徳之島岡前の勝伝宅で落ち着いていた8月26日、徳之島来島を知らされた愛加那が大島から子供2人を連れて西郷のもとを訪れた。久しぶりの親子対面を喜んでから数日後、さらに追い打ちをかけるように沖永良部島へ遠島する命令が届いた。これより前の7月下旬、鹿児島では弟たちが遠慮・謹慎などの処分を受け、西郷家の知行・家財は没収され、最悪の状態に追い込まれていた。

藩命で舟牢に入れられて、閏8月初め、徳之島岡前を出発し、14日に沖永良部島伊延(旧:ゆぬび・現:いのべ)に着いた。当初、牢が貧弱で風雨にさらされたので、健康を害した。しかし、10月、間切横目・土持政照が代官の許可を得て、自費で座敷牢を作ってくれたので、そこに移り住み、やっと健康を取り戻した。4月には同じ郷中の後輩が詰役として来島したので、西郷の待遇は一層改善された。この時西郷は沖永良部の人々に勉学を教えている。また、土持政照と一緒に酒を飲んでいる様子がこの島のサイサイ節という民謡に歌われている。

文久3年(1863年)7月、前年の生麦事件を契機に起きた薩英戦争の情報が入ると、処罰覚悟で鹿児島へ帰り、参戦しようとした。10月、土持がつくってくれた船に乗り、鹿児島へ出発しようとしていたとき、英艦を撃退したとの情報を得て、祝宴を催し喜んだ。来島まもなく始めた塾も元治元年(1864年)1月頃には20名程になった。やがて赦免召還の噂が流れてくると、『与人役大躰』『間切横目大躰』を書いて島役人のための心得とさせ、社倉設立の文書を作って土持に与え、飢饉に備えさせた。在島中も諸士との情報交換はかかさず、大島在番であった桂久武、琉球在番の米良助右衛門、真木保臣などと書簡を交わした。

この頃、本土では、薩摩の意見も取り入れ、文久2年(1862年)7月に松平春嶽が政事総裁職、徳川慶喜が将軍後見職となり(文久の幕政改革)、閏8月に会津藩主・松平容保が京都守護職、桑名藩主・松平定敬が京都所司代となって、幕権に回復傾向が見られる一方、文久3年(1863年)5月に長州藩の米艦砲撃事件、8月に奈良五条の天誅組の変と長州への七卿落ち(八月十八日の政変)、10月に生野の変など、開港に反対する攘夷急進派が種々の抵抗をして、幕権の失墜をはかっていた。

もともと公武合体派とはいっても、天皇のもとに賢侯を集めての中央集権をめざす薩摩藩の思惑と将軍中心の中央集権をめざす幕府の思惑は違っていたが、薩英戦争で活躍した旧精忠組の発言力の増大と守旧派の失脚を背景に、薩摩流の公武周旋をやり直そうとした久光にとっては、京大坂での薩摩藩の世評の悪化と公武周旋に動く人材の不足が最大の問題であった。この苦境を打開するために大久保利通(一蔵)や小松帯刀らの勧めもあって、西郷を赦免召還することにした。元治元年(1864年)2月21日、吉井友実・西郷従道(信吾)らを乗せた蒸気船胡蝶丸が沖永良部島和泊に迎えにきた。途中で大島龍郷に寄って妻子と別れ、喜界島遠島中の村田新八を伴って(村田の兄宛書簡あり。無断で連れ帰ったとも、そうではなかったともいう)帰還の途についた。

禁門の変前後

元治元年(1864年)2月28日に鹿児島に帰った西郷は足が立たなかった。29日、這いずりながら斉彬の墓参をしたという。3月4日、村田新八をともなって鹿児島を出帆し、14日に京都に到着し、19日に軍賦役(軍司令官)に任命された。京都に着いた西郷は薩摩が佐幕・攘夷派双方から非難されており、攘夷派志士だけではなく、世評も極めて悪いのに驚いた。そこで、藩の行動原則を朝旨に遵(したが)った行動と単純化し、攘夷派と悪評への緩和策を採ることで、この難局を乗り越えようとした[1]。

この当時、攘夷派および世人から最も悪評を浴びていたのが、薩摩藩と外夷との密貿易であった。文久3年(1863年)半ばに、南北戦争(1861年-1865年)により欧州の綿・茶が不足となり、日本綿・茶の買い付けが盛んに行なわれた結果、両品の日本からの輸出量が極端に増加した。このことから日本中の綿・茶値段は高騰し、薩摩藩の外夷との通商が物価高騰の原因であるとする風評ができたのである。世人は物価の高騰を怒ったのであるが、攘夷派は攘夷と唱えながら外夷と通商していること自体を怒ったのである。その結果、長州藩による薩摩藩傭船長崎丸撃沈事件、加徳丸事件が起きた[1]。

こうして形成された薩摩藩への悪評(世論も大きな影響を持っていた)は薩摩藩の京都・大坂での活動に大きな支障となったので、西郷は6月11日に大坂留守居・木場伝内に上坂中の薩摩商人の取締りを命じ[2]、往来手形を持参していない商人らにも帰国するよう命じ、併せて藩内での取締りも強化し、藩命を以て大商人らを上坂させぬように処置した[3]。

4月、西郷は御小納戸頭取・一代小番に任命された。池田屋事件からまもない6月27日、朝議で七卿赦免の請願を名目とする長州兵の入京が許可された。これに対し、西郷は薩摩は中立して皇居守護に専念すべしとし、7月8日の徳川慶喜の出兵命令を小松帯刀と相談のうえで断った。しかし、18日、長州勢(長州・因州・備前・浪人志士)が伏見・嵯峨・山崎の三方から京都に押し寄せ、皇居諸門で幕軍と衝突すると、西郷と伊地知正治らは乾御門で長州勢を撃退したばかりでなく、諸所の救援に薩摩兵を派遣して、長州勢を撃退した(禁門の変)。このとき、西郷は銃弾を受けて軽傷を負った。この事変で西郷らがとった中立の方針は、長州や幕府が朝廷を独占するのを防ぎ、朝廷をも中立の立場に導いたのであるが、長州勢からは来島又兵衛・久坂玄瑞・真木保臣ら多く犠牲者が出て、長州の薩摩嫌いを助長し、「薩奸会賊」と呼ばれるようになった。

第一次長州征伐前後

元治元年(1864年)7月23日に長州藩追討の朝命(第一次長州征伐)が出、24日に徳川慶喜が西国21藩に出兵を命じると、この機に乗じて薩摩藩勢力の伸張をはかるべく、それに応じた。8月、四国連合艦隊下関砲撃事件が起きた。次いで長州と四国連合艦隊の講和条約が結ばれ、幕府と四国代表との間にも賠償約定調印が交わされた。この間の9月中旬、西郷は大坂で勝海舟と会い、勝の意見を参考にして、長州に対して強硬策をとるのを止め、緩和策で臨むことにした。10月初旬、御側役・代々小番[注 4]となり、大島吉之助[注 5]から西郷吉之助に改めた。

10月12日、西郷は征長軍参謀に任命された。24日、大坂で征長総督・徳川慶勝にお目見えし、意見を具申したところ、長州処分を委任された。そこで、吉井友実・税所篤を伴い、岩国で長州方代表の吉川経幹(監物)と会い、長州藩三家老の処分を申し入れた。引き返して徳川慶勝に経過報告をしたのち、小倉に赴き、副総督・松平茂昭に長州処分案と経過を述べ、薩摩藩総督・島津久明にも経過を報告した。結局、西郷の妥協案に沿って収拾がはかられ、12月27日、征長総督が出兵諸軍に撤兵を命じ、この度の征討行動は終わった。収拾案中に含まれていた五卿処分も、中岡慎太郎らの奔走で、西郷の妥協案に従い、慶応元年(1865年)初頭に福岡藩の周旋で九州5藩に分移させるまで福岡で預かることで一応決着した。

第二次長州征伐と薩長同盟

慶応元年(1865年)1月中旬に鹿児島へ帰って藩主父子に報告を済ますと、人の勧めもあって、1月28日に家老座書役・岩山八太郎直温の二女・イト(絲子)と結婚した。この後、前年から紛糾していた五卿移転とその待遇問題を周旋して、2月23日に待遇を改善したうえで太宰府天満宮の延寿王院に落ち着かせることでやっと収束させた。これと平行して大久保利通・吉井孝輔らとともに九州諸藩連合のために久留米藩・福岡藩などを遊説していたが、3月中旬に上京した。この頃幕府は武力で勅命を出させ、長州藩主父子の出府、五卿の江戸への差し立て、参勤交代の復活の3事を実現させるために、2老中に4大隊と砲を率いて上京させ、強引に諸藩の宮門警備を幕府軍に交替させようとしていたが、それを拒否する勅書と伝奏が所司代に下され、逆に至急将軍を入洛させるようにとの命が下された。これらは幕権の回復を望まない西郷・大久保らの公卿工作によるものであった。

5月1日に西郷は坂本龍馬を同行して鹿児島に帰り、京都情勢を藩首脳に報告した。その後、幕府の征長出兵命令を拒否すべしと説いて藩論をまとめた。9日に大番頭・一身家老組[注 6]に任命された[4]。この頃、将軍・徳川家茂は、勅書を無視して、紀州藩主・徳川茂承以下16藩の兵約6万を率いて西下を開始し、兵を大坂に駐屯させたのち、閏5月22日に京都に入った。翌23日、家茂は参内して武力を背景に長州再征を奏上したが、許可されなかった。6月、鹿児島入りした中岡慎太郎は、西郷に薩長の協力と和親を説き、下関で桂小五郎(木戸孝允)と会うことを約束させた。しかし、西郷は大久保から緊迫した書簡を受け取ったので、下関寄港を取りやめ、急ぎ上京した。

この間、京大坂滞在中の幕府幹部は兵6万の武力を背景に一層強気になり、長州再征等のことを朝廷へ迫った。これに対し、西郷は幕府の脅しに屈せず、6月11日、幕府の長州再征に協力しないように大久保に伝え、そのための朝廷工作を進めさせた。それに加え、24日には京都で坂本龍馬と会い、長州が欲している武器・艦船の購入を薩摩名義で行うこと承諾し、薩長和親の実績をつくった。また、幕府の兵力に対抗する必要を感じ、10月初旬に鹿児島へ帰り、15日に小松帯刀とともに兵を率いて上京した。この頃、長州から兵糧米を購入することを龍馬に依頼したが、これもまた薩長和親の実績づくりであった。この間、黒田清隆(了介)を長州へ往還させ薩長同盟の工作も重ねさせた。

9月16日、英・仏・蘭三カ国の軍艦8隻が兵庫沖に碇泊し、兵庫開港を迫った。一方、京都では、武力を背景にした脅迫にひるみ、9月21日、朝廷は幕府に長州再征の勅許を下した。また、10月1日に前尾張藩主・徳川慶勝から出された条約の勅許と兵庫開港勅許の奏請も、一旦は拒否したが、将軍辞職をほのめかしと朝廷への武力行使も辞さないとの幕府及び徳川慶喜の脅迫に屈して、条約は勅許するが、兵庫開港は不許可という内容の勅書を下した。これは強制されたものであったとはいえ、安政以来の幕府の念願の実現であり、国是の変更という意味でも歴史上の大きな決定であった。

慶応2年(1866年)1月8日、西郷は村田新八・大山成美(通称は彦八、大山巌の兄)を伴って、上京してきた桂小五郎を伏見に出迎え、翌9日、京都に帰って二本松藩邸に入った。21日(22日という説もある)、西郷は小松帯刀邸で桂小五郎と薩長提携六ヶ条を密約し、坂本龍馬がその提携書に裏書きをした(薩長同盟)。その直後、龍馬が京都の寺田屋で幕吏に襲撃されると、西郷の指示で、薩摩藩邸が龍馬を保護した。その後、3月4日に小松帯刀・桂久武・吉井友実・坂本龍馬夫妻(西郷が仲人をした)らと大坂を出航し、11日に鹿児島へ着いた。4月、藩政改革と陸海軍の拡張を進言し、それが入れられると、5月1日から小松・桂らと藩政改革にあたった。

第二次長州征伐は、6月7日の幕府軍艦による上ノ関砲撃から始まった。大島口・芸州口・山陰口・小倉口の四方面で戦闘が行われ、芸州口は膠着したが、大島口・小倉口は高杉晋作の電撃作戦と奇兵隊を中心とする諸隊の活躍で勝利し、大村益次郎が指揮した山陰口も連戦連勝し、幕府軍は惨敗続きであった。鹿児島にいた西郷は、7月9日に朝廷に出す長州再征反対の建白を起草し、藩主名で幕府へ出兵を断る文書を提出させた。一方、幕府は、7月30日に将軍・徳川家茂が大坂城中で病死したので、喪を秘し、8月1日の小倉口での敗北を機に、敗戦処理と将軍継嗣問題をかたづけるべく、朝廷に願い出て、21日に休戦の御沙汰書を出してもらった。将軍の遺骸を海路江戸へ運んだ幕府は、12月25日の孝明天皇の崩御を機に解兵の御沙汰書を得て公布し、この戦役を終わらせた。この間の7月12日、西郷に嫡男・寅太郎が誕生し、9月に大目付・陸軍掛・家老座出席に任命された[4][注 7]。 しかし病気を理由に大目付役は返上した。

大政奉還と王政復古

慶応3年(1867年)3月上旬、村田新八・中岡慎太郎らを先発させ、大村藩・平戸藩などを遊説させた。3月25日、西郷は久光を奉じ、薩摩の精鋭700名(城下1番小隊から6番小隊)を率いて上京した。5月に京都の薩摩藩邸と土佐藩邸で相次いで開催された四侯会議の下準備をした。5月21日、中岡慎太郎の仲介によって、京都の小松帯刀邸にて、土佐藩の乾退助、谷干城らと、薩摩藩の西郷、吉井幸輔らが武力討幕を議して、薩土討幕の密約(薩土密約)を結ぶ(この密約は、戊辰戦争の際に乾が迅衝隊を率いて出征し達成されることとなる)。6月15日、西郷は山縣有朋を訪問し、武力討幕の決意を告げた。16日、西郷と小松帯刀・大久保利通・伊地知正治・山縣有朋・品川弥二郎らが会し、改めて薩長同盟の誓約をした。その後、江戸市内へ伊牟田尚平・益満休之助・相楽総三らを派遣し、破壊工作(江戸や近辺の放火・強盗による人心攪乱)を行わせ幕府を挑発した。22日には西郷が坂本龍馬・後藤象二郎・福岡孝弟らと会し、薩土盟約が成立した。

9月7日、久光の三男・島津珍彦(うずひこ)が兵約1,000名を率いて大坂に着いた。9月9日、後藤が来訪して坂本龍馬案にもとづく大政奉還建白書を提出するので、挙兵を延期するように求めたが、西郷は拒否した(後日了承した)。土佐藩(前藩主・山内容堂)から提出された建白書を見た将軍・徳川慶喜は、10月14日に大政奉還の上奏を朝廷に提出させた。ところが、同じ14日に、討幕と会津・桑名誅伐の密勅が下り、西郷・小松・大久保・品川らはその請書を出していた(この請書には西郷吉之助武雄と署名している[4])。15日、朝廷から大政奉還を勅許する旨の御沙汰書が出された。

密勅を持ち帰った西郷は、桂久武らの協力で藩論をまとめ、11月13日、藩主・島津忠義を奉じ、兵約3,000名を率いて鹿児島を発した。途中で長州と出兵時期を調整し、三田尻を発して、20日に大坂、23日に京都に着いた。長州兵約700名も29日に摂津打出浜に上陸して、西宮に進出した。またこの頃、芸州藩も出兵を決めた。諸藩と出兵交渉をしながら、西郷は、11月下旬頃から有志に王政復古の大号令発布のための工作を始めさせた。12月9日、薩摩・芸州・尾張・越前に宮中警護のための出兵命令が出され、会津・桑名兵とこれら4藩兵が宮中警護を交替すると、王政復古の大号令が発布された。

戊辰戦争

慶応4年(1868年)1月3日、大坂の旧幕軍が上京を開始し、幕府の先鋒隊と薩長の守備隊が衝突し、鳥羽・伏見の戦いが始まった(戊辰戦争開始)。西郷はこの3日には伏見の戦線、5日には八幡の戦線を視察し、戦況が有利になりつつあるのを確認した。6日、徳川慶喜は松平容保・松平定敬以下、老中・大目付・外国奉行ら少数を伴い、大坂城を脱出して、軍艦「開陽丸」に搭乗して江戸へ退去した。新政府は7日に慶喜追討令を出し、9日に有栖川宮熾仁親王を東征大総督(征討大総督)に任じ、東海・東山・北陸三道の軍を指揮させ、東国経略に乗り出した。

西郷は2月12日に東海道先鋒軍の薩摩諸隊差引(司令官)、14日に東征大総督府下参謀(参謀は公家が任命され、下参謀が実質上の参謀)に任じられると、独断で先鋒軍(薩軍一番小隊隊長・中村半次郎、二番小隊隊長・村田新八、三番小隊隊長・篠原国幹らが中心)を率いて先発し、2月28日には東海道の要衝箱根を占領した。占領後、三島を本陣としたのち、静岡に引き返した。3月9日、静岡で徳川慶喜の使者・山岡鉄舟と会見し、徳川処分案7ヶ条を示した。その後、大総督府からの3月15日江戸総攻撃の命令を受け取ると、静岡を発し、11日に江戸に着き、池上本門寺の本陣に入った。

3月13日、14日、勝海舟と会談し、江戸城明け渡しについての交渉をした。当時、薩摩藩の後ろ盾となっていたイギリスは日本との貿易に支障が出ることを恐れて江戸総攻撃に反対していたため、「江戸城明け渡し」は新政府の既定方針だった。橋本屋での2回目の会談で海舟から徳川処分案を預かると、総攻撃中止を東海道軍・東山道軍に伝えるように命令し、自らは江戸を発して静岡に赴き、12日、大総督・有栖川宮に謁見して勝案を示し、さらに静岡を発して京都に赴き、20日、朝議にかけて了承を得た。江戸へ帰った西郷は4月4日、勅使・橋本実梁らと江戸城に乗り込み、田安慶頼に勅書を伝え、4月11日に江戸城明け渡し(無血開城)が行なわれた。

江戸幕府を滅亡させた西郷は、仙台藩(伊達氏)を盟主として樹立された奥羽越列藩同盟との「東北戦争」に臨んだ。 5月上旬、上野の彰義隊の打破と東山軍の白河城攻防戦の救援のどちらを優先するかに悩み、江戸守備を他藩にまかせて、配下の薩摩兵を率いて白河応援に赴こうとしたが、大村益次郎の反対にあい、上野攻撃を優先することにした。5月15日、上野戦争が始まり、正面の黒門口攻撃を指揮し、これを破った。5月末、江戸を出帆。京都で戦況を報告し、6月9日に藩主・島津忠義に随って京都を発し、14日に鹿児島に帰着した。この頃から健康を害し、日当山温泉で湯治した[4]。

北陸道軍の戦況が思わしくないため、西郷の出馬が要請され、7月23日、薩摩藩北陸出征軍の総差引(司令官)を命ぜられ、8月2日に鹿児島を出帆し、10日に越後柏崎に到着した。来て間もない14日、新潟五十嵐戦で負傷した二弟の吉二郎の訃報を聞いた。藩の差引の立場から北陸道本営(新発田)には赴かなかったが、総督府下参謀の黒田清隆・山縣有朋らは西郷のもとをしばしば訪れた。新政府軍に対して連戦連勝を誇った庄内藩も、仙台藩、会津藩が降伏すると9月27日に降伏し、ここに「東北戦争」は新政府の勝利で幕を閉じた。このとき、西郷は黒田に指示して、庄内藩に寛大な処分をさせた。この後、庄内を発し、江戸・京都・大坂を経由して、11月初めに鹿児島に帰り、日当山温泉で湯治した。

薩摩藩参政時代

明治2年(1869年)2月25日、藩主・島津忠義が自ら日当山温泉まで来て要請したので、26日、鹿児島へ帰り、参政・一代寄合となった。以来、藩政の改革[注 8]や兵制の整備(常備隊の設置)を精力的に行い、戊辰参戦の功があった下級武士の不満解消につとめた。文久2年(1862年)に沖永良部島遠島・知行没収になって以来、無高であった(役米料だけが与えられていた)が、3月、許されて再び高持ちになった。

5月1日、箱館戦争の応援に総差引として藩兵を率いて鹿児島を出帆した。途中、東京で出張許可を受け、5月25日、箱館に着いたが、18日に箱館・五稜郭が開城し、戦争はすでに終わっていた(戊辰戦争の終了)。帰路、東京に寄った際、6月2日の王政復古の功により、賞典禄永世2,000石を下賜された。このときに残留の命を受けたが、断って、鹿児島へ帰った。7月、鹿児島郡武村(現在の鹿児島市武二丁目の西郷公園)に屋敷地を購入した。9月26日、正三位に叙せられた。12月に藩主名で位階返上の案文を書き、このときに隆盛という名を初めて用いた[4]。明治3年(1870年)1月18日に参政を辞め、相談役になり、7月3日に相談役を辞め、執務役となっていたが、太政官から鹿児島藩大参事に任命された(辞令交付は8月)。

大政改革と廃藩置県

明治3年(1870年)2月13日、西郷は村田新八・大山巌・池上四郎らを伴って長州藩に赴き、奇兵隊脱隊騒擾の状を視察し、奇兵隊からの助援の請を断わり、藩知事・毛利広封に謁見したのちに鹿児島へ帰った。同年7月27日、鹿児島藩士で集議院徴士の横山安武(森有礼の実兄)が時勢を非難する諫言書を太政官正院の門に投じて自刃した。これに衝撃を受けた西郷は、役人の驕奢により新政府から人心が離れつつあり、薩摩人がその悪弊に染まることを憂慮して[5]、薩摩出身の心ある軍人・役人だけでも鹿児島に帰らせるために、9月、池上を東京へ派遣した[6]。 12月、危機感を抱いた政府から勅使・岩倉具視、副使・大久保利通が西郷の出仕を促すために鹿児島へ派遣され、西郷と交渉したが難航し、欧州視察から帰国した西郷従道の説得でようやく政治改革のために上京することを承諾した。

明治4年(1871年)1月3日、西郷と大久保は池上を伴い「政府改革案」を持って上京するため鹿児島を出帆した。8日、西郷・大久保らは木戸を訪問して会談した。16日、西郷・大久保・木戸・池上らは三田尻を出航して土佐に向かった。17日、西郷一行は土佐に到着し、藩知事・山内豊範、大参事・板垣退助と会談した。22日、西郷・大久保・木戸・板垣・池上らは神戸に着き、大坂で山縣有朋と会談し、一同そろって大坂を出航し東京へ向かった。東京に着いた一行は2月8日に会談し、御親兵の創設を決めた。この後、池上を伴って鹿児島へ帰る途中、横浜で東郷平八郎に会い、勉強するように励ました[7]。

2月13日に鹿児島藩・山口藩・高知藩の兵を徴し、御親兵に編成する旨の命令が出されたので、西郷は忠義を奉じ、常備隊4大隊約5,000名を率いて上京し、4月21日に東京市ヶ谷旧尾張藩邸に駐屯した。この御親兵以外にも東山道鎮台(石巻)と西海道鎮台(小倉)を設置し、これらの武力を背景に、6月25日から内閣人員の入れ替えを始めた。このときに西郷は再び正三位に叙せられた。7月5日、制度取調会の議長となり、6日に委員の決定権委任の勅許を得た。これより新官制・内閣人事・廃藩置県等を審議し、大久保・木戸らと公私にわたって議論し、朝議を経て、14日、明治天皇が在京の藩知事(旧藩主)を集め、廃藩置県の詔書を出した。また、この間に新官制の決定や内閣人事も順次行い、7月29日頃には以下のような顔ぶれになった[8](ただし、外務卿岩倉の右大臣兼任だけは10月中旬にずれ込んだ)。

- 太政大臣(三条実美)

- 右大臣兼外務卿(岩倉具視)

- 参議(西郷隆盛、木戸孝允、板垣退助、大隈重信)

- 大蔵卿(大久保利通)

- 文部卿(大木喬任)

- 兵部大輔(山縣有朋)

この経緯については、各藩主に御親兵として兵力を供出させ、手足をもいだ状態で、廃藩置県をいきなり断行するなど言わば騙し討ちに近い形であった。

留守政府

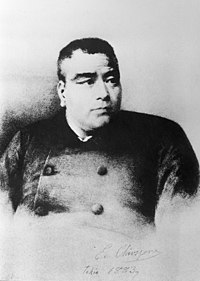

軍服姿の西郷隆盛

床次正精作。床次は薩摩藩士族で西郷とは面識があり、床次の描く西郷の顔は実物によく似ていると言われている。

明治4年(1871年)11月12日、三条・西郷らに留守内閣(留守政府)をまかせ、特命全権大使・岩倉具視、副使・木戸孝允、大久保利通、伊藤博文、山口尚芳ら外交使節団が条約改正のために横浜から欧米各国へ出発した(随員中に宮内大丞・村田新八もいた)。西郷らは明治4年(1871年)からの官制・軍制の改革および警察制度の整備を続け、同5年(1872年)2月には兵部省を廃止して陸軍省・海軍省を置き、3月には御親兵を廃止して近衛兵を置いた。5月から7月にかけては天皇の関西・中国・西国巡幸に随行した。鹿児島行幸から帰る途中、近衛兵の紛議を知り、急ぎ帰京して解決をはかり、7月29日、陸軍元帥兼参議に任命された。このときに山城屋事件で多額の軍事費を使い込んだ近衛都督・山縣有朋が辞任したため、薩長の均衡をとるために三弟・西郷従道を近衛副都督から解任した。明治6年(1873年)5月に徴兵令が実施されたのに伴い、元帥が廃止されたので、西郷は陸軍大将兼参議となった。

なお、明治4年(1871年)11月の岩倉使節団出発から明治6年(1873年)9月の岩倉帰国までの間に西郷主導留守内閣が施行した主な政策は以下の通りである。

明治六年政変

対朝鮮(当時は李氏朝鮮)問題は、明治元年(1868年)に李朝が維新政府の国書の受け取りを拒絶したことが発端だが、この国書受け取りと朝鮮との修好条約締結問題は留守内閣時にも一向に進展していなかった。そこで、進展しない原因とその対策を知る必要があって、西郷と板垣退助・副島種臣らは、調査のために、明治5年(1872年)8月15日に池上四郎・武市正幹・彭城中平を清国・ロシア・朝鮮探偵として満洲に派遣し[9]、27日に北村重頼・河村洋与・別府晋介(景長)を花房外務大丞随員(実際は変装しての探偵)として釜山に派遣した[10]。

明治6年(1873年)の対朝鮮問題をめぐる政府首脳の軋轢は、6月に外務少記・森山茂が釜山から帰国後、李朝政府が日本の国書を拒絶したうえ、使節を侮辱し、居留民の安全が脅かされているので、朝鮮から撤退するか、武力で修好条約を締結させるかの裁決が必要であると報告し、それを外務少輔・上野景範が内閣に議案として提出したことに始まる。この議案は6月12日から7参議により審議された。

議案は当初、板垣が武力による修好条約締結(征韓論)を主張したのに対し、西郷は武力を不可として、自分が旧例の服装で全権大使になる(遣韓大使論)と主張して対立した。しかし、数度に及ぶ説得で、方法・人選で反対していた板垣と外務卿の副島が8月初めに西郷案に同意した。西郷派遣については、16日に三条実美の同意を得て、17日の閣議で決定された。しかし、三条が天皇に報告したとき、「岩倉具視の帰朝を待って、岩倉と熟議して奏上せよ」との勅旨があったので、発表は岩倉帰国まで待つことになった。

以上の時点までは、西郷・板垣・副島らは大使派遣の方向で事態は進行するものと考えていた。ところが、9月、岩倉が帰国すると、先に外遊から帰国していた木戸孝允・大久保利通らの内治優先論が表面化してきた。大久保らが参議に加わった9月14日の閣議では大使派遣問題は議決できず、15日の再議で西郷派遣に決定した。しかし、これに反対する木戸孝允・大久保利通・大隈重信・大木喬任らの参議が辞表を提出し、右大臣・岩倉も辞意を表明する事態に至った。これを憂慮した三条は18日夜、急病になり、岩倉が太政大臣代行になった。そこで、西郷と板垣退助・副島種臣・江藤新平らは岩倉邸を訪ねて、閣議決定の上奏裁可を求めたが、岩倉は了承しなかった。

9月23日、西郷が陸軍大将兼参議・近衛都督を辞し、位階も返上すると上表したのに対し、すでに宮中工作を終えていた岩倉は、閣議の決定とは別に西郷派遣延期の意見書を天皇に提出した。翌24日に天皇が岩倉の意見を入れ、西郷派遣を無期延期するとの裁可を出したので、西郷は辞職した。このとき、西郷の参議・近衛都督辞職は許可されたが、陸軍大将辞職と位階の返上は許されなかった。

翌25日になると、板垣・副島・後藤・江藤らの参議も辞職した。この一連の辞職に同調して、征韓論・遣韓大使派の林有造・桐野利秋・篠原国幹・淵辺群平・別府晋介・河野主一郎・辺見十郎太をはじめとする政治家・軍人・官僚600名余が次々に大量に辞任した。この後も辞職が続き、遅れて帰国した村田新八・池上四郎らもまた辞任した(明治六年政変)。

このとき、西郷の推挙で兵部大輔・大村益次郎の後任に補されながら、能力不足と自覚して、先に下野していた前原一誠は「宜シク西郷ノ職ヲ復シテ薩長調和ノ実ヲ計ルベシ、然ラザレバ、賢ヲ失フノ議起コラント」[11]という内容の書簡を太政大臣・三条実美に送り、明治政府の前途を憂えた。

私学校

下野した西郷は、明治6年(1873年)11月10日、鹿児島に帰着し、以来、大半を武村の自宅で過ごした。猟に行き、山川の鰻温泉で休養していた明治7年(1874年)3月1日、佐賀の乱で敗れた江藤新平が来訪し、翌日、指宿まで見送った(江藤は土佐で捕まった)。これ以前の2月に閣議で台湾征討が決定した。この征討には木戸が反対して参議を辞めたが、西郷も反対していた。しかし、4月、台湾征討軍の都督となった三弟・西郷従道の要請を入れ、やむなく鹿児島から徴募して、兵約800名を長崎に送った。

西郷の下野に同調した軍人・警吏が相次いで帰県した明治6年末以来、鹿児島県下は無職の血気多き壮年者がのさばり、それに影響された若者に溢れる状態になった[注 9]。 そこで、これを指導し、統御しなければ、壮年・若者の方向を誤るとの考えから、有志者が西郷にはかり、県令・大山綱良の協力を得て、明治7年6月頃に旧厩跡に私学校がつくられた[12]。 私学校は篠原国幹が監督する銃隊学校、村田新八が監督する砲隊学校、村田が監督を兼任した幼年学校(章典学校)があり、県下の各郷ごとに分校が設けられた。この他に、明治8年(1875年)4月には西郷と大山県令との交渉で確保した荒蕪地に、桐野利秋が指導し、永山休二・平野正介らが監督する吉野開墾社(旧陸軍教導団生徒を収容)もつくられた。

明治8年から明治9年(1876年)にかけての西郷は自宅でくつろぐか、遊猟と温泉休養に行っていることが多い。西郷の影響下にある私学校が整備されて、私学校党が県下最大の勢力となると、大山綱良もこの力を借りることなしには県政が潤滑に運営できなくなり、私学校党人士を県官や警吏に積極的に採用し、明治8年11月と翌年4月には西郷に依頼して区長や副区長を推薦して貰った。このようにして別府晋介・辺見十郎太・河野主一郎・小倉壮九郎(東郷平八郎の兄)らが区長になり、私学校党が県政を牛耳るようになると、政府は以前にもまして、鹿児島県は私学校党の支配下に半ば独立状態にあると見なすようになった。

西南戦争前夜

明治9年(1876年)3月に廃刀令が出、8月に金禄公債証書条例が制定されると、士族とその子弟で構成される私学校党の多くは、徴兵令で代々の武人であることを奪われたことに続き、帯刀と知行地という士族最後の特権をも奪われたことに憤慨した。10月24日の熊本県士族の神風連の乱、27日の福岡県士族の秋月の乱、28日の萩の乱もこれらの特権の剥奪に怒っておきたものであった。11月、西郷は日当山温泉でこれら決起の報を聞き、

- 前原一誠らの行動を愉快なものとして受け止めている。

- 今帰ったら若者たちが逸るかもしれないので、まだこの温泉に止まっている。

- 今まで一切自分がどう行動するかを見せなかったが、起つと決したら、天下の人々を驚かすようなことをするつもりである。

などを記した書簡を桂久武に出し、「起つと決する」時期を待っていることを知らせた。この「起つと決する」が国内での決起を意味するのか、西郷がこの時期に一番気にかけていた対ロシア問題での決起を意味していたのかは判然としない。

一方、政府は、鹿児島県士族の反乱がおきるのではと警戒し、年末から1月にかけて、

- 鹿児島県下の火薬庫(弾薬庫ともいう)から火薬・弾薬を順次船で運びださせる。

- 大警視・川路利良らが24名の巡査を、県下の情報探索・私学校の瓦解工作・西郷と私学校を離間させるなどの目的で、帰郷の名目のもと鹿児島に派遣する。

などの処置をした。

これに対し、私学党は、すでに陸海軍省設置の際に武器や火薬・弾薬の所管が陸海軍に移っていて、陸海軍がそれを運び出す権利を持っていたにもかかわらず、本来、これらは旧藩士の醵出金で購入したり、つくったりしたものであるから、鹿児島県士族がいざというときに使用するものであるという意識を強く持っていた[13]。 また、多数の巡査が一斉に帰郷していることは不審であり、その目的を知る必要があると考えていた。なお、まだこの時点では、川路利良が中原尚雄に、瓦解・離間ができないときは西郷を「シサツ」せよ、と命じていたことは知られていなかった(山縣有朋は私学校党が「視察」を「刺殺」と誤解したのだと言っている。明治5年の池上らの満洲の偵察を公文書で「満洲視察」と表現していることから見ると、この当時の官僚用語としての「視察」には「偵察」の意もあった)。

挙兵

明治10年(1877年)1月20日頃、西郷は、この時期に私学校生徒が火薬庫を襲うなどとは夢にも思わず、大隅半島の小根占で狩猟をしていた。一方、政府は鹿児島県士族の反乱を間近しと見て、1月28日に山縣有朋が熊本鎮台に電報で警戒命令を出した。29日、従来は危険なために公示したうえで標識を付けて白昼運び出していたのに、陸軍の草牟田火薬庫の火薬・弾薬が夜中に公示も標識もなしに運び出され、赤龍丸に移された。これに触発されて私学校生徒が、同火薬庫を襲った。

官軍と西郷軍の激突を描いた 浮世絵。中央に西郷隆盛が描かれている。

2月1日、小根占にいた西郷のもとに四弟・小兵衞が私学校幹部らの使者として来て、谷口登太が中原尚雄から西郷刺殺のために帰県したと聞き込んだこと、私学校生徒による火薬庫襲撃がおきたことなどを話した。これを聞いて西郷が鹿児島へ帰ると、身辺警護に駆けつける人数が時とともに増え続けた。3日に中原が捕らえられ、4日に拷問によって自供すると[注 11]、6日に私学校本校で大評議が開かれ、政府問罪のために大軍を率いて上京することに決したので、翌7日に県令・大山綱良に上京の決意を告げた。このようにして騒然となっていた9日、川村純義が高雄丸で西郷に面会に来たので、会おうとしたが、会えなかった。同日、巡査たちとは別に、大久保が派遣した野村綱が県庁に自首した[注 12]。 西郷は、その自白内容から、大久保も刺殺に同意していると考えるようになったらしい。

募兵、新兵教練が終わった13日、大隊編制が行われ、一番大隊指揮長に篠原国幹、二番大隊指揮長に村田新八、三番大隊指揮長に永山弥一郎、四番大隊指揮長に桐野利秋、五番大隊指揮長に池上四郎が選任され、桐野が総司令を兼ねることになった。淵辺群平は本営附護衛隊長となり、狙撃隊を率いて西郷を護衛することになった。別府は加治木で別に2大隊を組織してその指揮長になった[注 13]。 翌14日、私学校本校横の練兵場[注 14]で西郷による正規大隊の閲兵式が行われた。15日、薩軍の一番大隊が鹿児島から先発し(西南戦争開始)、17日、西郷も鹿児島を出発し、加治木・人吉を経て熊本へ向かった。

熊本の戦い

2月20日、別府晋介の大隊が川尻に到着。熊本鎮台偵察隊と衝突し、これを追って熊本へ進出した。21日、相次いで到着した薩軍の大隊は順次、熊本鎮台を包囲して戦った。22日、早朝から熊本城を総攻撃した。昼過ぎ、西郷が世継宮に到着した。政府軍一部の植木進出を聞き、午後3時に村田三介・伊東直二の小隊が植木に派遣され、夕刻、伊東隊の岩切正九郎が乃木希典率いる第14連隊の軍旗を分捕った。一方、総攻撃した熊本城は堅城で、この日の状況から簡単には陥ちないと見なされた。夜、本荘に本営を移し、ここでの軍議でもめているうちに、政府軍の正規旅団は本格的に南下し始めた。この軍議では一旦は篠原らの全軍攻城策に決したが、のちの再軍議で熊本城を長囲し、一部は小倉を電撃すべしと決し、翌23日に池上四郎が数箇小隊を率いて出発したが、南下してきた政府軍と田原・高瀬・植木などで衝突し、電撃作戦は失敗した。

これより、南下政府軍、また上陸してくると予想される政府軍、熊本鎮台に対処するために、熊本城攻囲を池上にまかせ、永山弥一郎に海岸線を抑えさせ、篠原国幹(六箇小隊)は田原に、村田新八・別府晋介(五箇小隊)は木留に、桐野利秋(三箇小隊)は山鹿に分かれ、政府軍を挟撃して高瀬を占領することにした。しかし、いずれも勝敗があり、戦線が膠着した。

3月1日から始まった田原をめぐる戦い(田原坂・吉次など)は、この戦争の分水嶺になった激戦で、篠原国幹ら勇猛の士が次々と戦死した。このような犠牲を払ってまで守っていた田原坂であったが、20日に、兵の交替の隙を衝かれ、政府軍に奪われた。この戦いに敗れた原因は多々あるが、主なものでは、砲・小銃が旧式で、しかも不足、火薬・弾丸・砲弾の圧倒的な不足、食料などの輜重の不足があげられる。これらは西南戦争を通じて薩軍が持っていた弱点でもある。こうして田原方面から引き上げ、その後部線を保守している間に、上陸した政府背面軍に敗れた永山弥一郎が御船で自焚・自刃し、4月8日には池上四郎が安政橋口の戦いで敗れて、政府背面軍と鎮台の連絡を許すと、薩軍は腹背に敵を受ける形になった。そこで、この窮地を脱するために、14日、熊本城の包囲を解いて木山に退却した。この間、本営は本荘から3月16日に二本木、4月13日に木山、4月21日に矢部浜町と移され、西郷もほぼそれとともに移動したが、戦闘を直接に指揮しているわけでもないので、薩摩・大隅・日向の三州に蜷踞することを決めた4月15日の軍議に出席していたこと以外、目立った動向の記録はない。

薩軍は浜町で大隊を中隊に編制し直し、隊名を一新したのち、椎葉越えして、新たな根拠地と定めた人吉へ移動した。4月27日、一日遅れで桐野利秋が江代に着くと、翌28日に軍議が開かれ、各隊の部署を定め、日を追って順次、各地に配備した。これ以来、人吉に本営を設け、ここを中心に政府軍と対峙していたが、衆寡敵せず、徐々に政府軍に押され、人吉も危なくなった。そこで本営を宮崎に移すことにした。西郷は池上四郎に護衛され、5月31日、桐野利秋が新たな根拠地としていた軍務所(もと宮崎支庁舎)に着いた。ここが新たな本営となった。この軍務所では、桐野の指示で、薩軍の財政を立て直すための大量の軍票(西郷札)がつくられた。

宮崎の戦い

人吉に残った村田新八は、6月17日、小林に拠り、振武隊・破竹隊・行進隊・佐土原隊の約1,000名を指揮し、1ヶ月近く政府軍と川内川を挟んで小戦を繰り返した。7月10日、政府軍が加久藤・飯野に全面攻撃を加えてきたので、支えようとしたが支えきれず、高原麓・野尻方面へ退却した。小林も11日に政府軍の手に落ちた。17日と21の両日、堀与八郎が延岡方面にいた薩兵約1,000名を率いて高原麓を奪い返すために政府軍と激戦をしたが、これも勝てず、庄内、谷頭へ退却した。 24日、村田は都城で政府軍六箇旅団と激戦をしたが、兵力の差は如何ともしがたく、これも大敗して、宮崎へ退いた(都城の戦い)。

31日、桐野・村田らは諸軍を指揮して宮崎で戦ったが、再び敗れ、薩軍は広瀬・佐土原へ退いた(宮崎の戦い)。8月1日、薩軍が佐土原で敗れたので、政府軍は宮崎を占領した。宮崎から退却した西郷は、2日、延岡大貫村に着き、ここに9日まで滞在した。2日に高鍋が陥落し、3日から美々津の戦いが始まった。このとき、桐野利秋は平岩、村田新八は富高新町、池上四郎は延岡にいて諸軍を指揮したが、4日、5日ともに敗れた。6日、西郷は教書を出し、薩軍を勉励した。7日、池上の指示で火薬製作所・病院を熊田に移し、ここを本営とした。西郷は10日から本小路・無鹿・長井村笹首と移動し、14日に長井村可愛に到着し、以後、ここに滞在した[15]。その間の12日、参軍・山縣有朋は政府軍の延岡攻撃を部署した。同日、桐野・村田・池上は長井村から来て延岡進撃を部署し、本道で指揮したが、別働第二旅団・第三旅団・第四旅団・新撰旅団・第一旅団に敗れたので、延岡を総退却し、和田峠に依った。

8月15日、和田峠を中心に布陣し、政府軍に対し、西南戦争最後の大戦を挑んだ。早朝、西郷が初めて陣頭に立ち、自ら桐野・村田・池上・別府ら諸将を随えて和田峠頂上で指揮したが、大敗して延岡の回復はならず、長井村へ退いた。これを追って政府軍は長井包囲網をつくった。16日、西郷は解軍の令を出し、書類・陸軍大将の軍服を焼いた。この後、負傷者や諸隊の降伏が相次いだ。残兵とともに、三田井まで脱出してから今後の方針を定めると決し、17日夜10時、長井村を発し、可愛嶽(えのたけ)に登り、包囲網からの突破を試みた。突囲軍は精鋭300-500名で、前軍は河野主一郎・辺見十郎太、中軍は桐野・村田、後軍は中島健彦・貴島清が率い、池上と別府が約60名を率いて西郷隆盛を護衛した[15][注 15]。 突囲が成功した後、宮崎・鹿児島の山岳部を踏破すること10余日、鹿児島へ帰った。

城山決戦

9月1日、突囲した薩軍は鹿児島に入り、城山を占拠した。一時、薩軍は鹿児島城下の大半を制したが、上陸展開した政府軍が3日に城下の大半を制し、6日には城山包囲態勢を完成させた。19日、山野田一輔・河野主一郎が西郷の救命のためであることを隠し、挙兵の意を説くためと称して、軍使となって参軍・川村純義のもとに出向き、捕らえられた。22日、西郷は城山決死の檄を出した。23日、西郷は、山野田が持ち帰った川村からの返事を聞き、参軍・山縣有朋からの自決を勧める書簡を読んだが、返事を出さなかった。

9月24日、午前4時、政府軍が城山を総攻撃したとき、西郷と桐野利秋・桂久武・村田新八・池上四郎・別府晋介・辺見十郎太ら将士40余名は洞前に整列し、岩崎口に進撃した。まず国分寿介(『西南記伝』では小倉壮九郎)が剣に伏して自刃した。桂久武が被弾して斃れると、弾丸に斃れる者が続き、島津応吉久能邸門前で西郷も股と腹に被弾した。西郷は別府晋介を顧みて「晋どん、晋どん、もう、ここらでよか」と言い、将士が跪いて見守る中、襟を正し、跪座し遙かに東に向かって拝礼した。遙拝が終わり、別府は「ごめんなったもんし(御免なっ給もんし=お許しください)」と叫んで西郷の首を刎ねた。享年51(満49歳没)。

西郷の首はとられるのを恐れ、折田正助邸門前に埋められた[注 16]。西郷の死を見届けると、残余の将士は岩崎口に進撃を続け、私学校の一角にあった塁に籠もって戦ったのち、自刃、刺し違え、あるいは戦死した。

午前9時、城山の戦いが終わると大雨が降った。雨後、浄光明寺跡で山縣有朋と旅団長ら立ち会いのもとで検屍が行われた。西郷の遺体は毛布に包まれたのち、木櫃に入れられ、浄光明寺跡に埋葬された(現在の南洲神社の鳥居附近)。このときは仮埋葬であったために墓石ではなく木標が建てられた。木標の姓名は県令・岩村通俊が記した[16]。明治12年(1879年)、浄光明寺跡の仮埋葬墓から南洲墓地のほぼ現在の位置に改葬された。また、西郷の首も戦闘終了後に発見され、総指揮を執った山縣有朋の検分ののちに手厚く葬られた[注 17]。

死後

明治10年(1877年)2月25日に「行在所達第四号」で官位を褫奪(ちだつ)され、死後、賊軍の将として遇された。その後、西郷の人柄を愛した明治天皇の意向や黒田清隆らの努力があって明治22年(1889年)2月11日、大日本帝国憲法発布に伴う大赦で赦され、正三位を追贈された。明治天皇は西郷の死を聞いた際にも「西郷を殺せとは言わなかった」と洩らしたとされるほど西郷のことを気に入っていたようである。戒名は、南州寺殿威徳隆盛大居士。

人物

愛称

「西郷どん」とは「西郷殿」の鹿児島弁表現(現地での発音は「セゴドン」に近い)であり、目上の者に対する敬意だけでなく、親しみのニュアンスも込められている。また「うどさぁ」と言う表現もあるが、これは鹿児島弁で「偉大なる人」と言う意味である。最敬意を表した呼び方は「南洲翁」である。

- 「うーとん」「うどめ」などのあだ名の由来

- 「うどめ」とは「巨目」という意味である。西郷は肖像画にもあるように、目が大きく、しかも黒目がちであった。その眼光と黒目がちの巨目でジロッと見られると、桐野のような剛の者でも舌が張り付いて物も言えなかったという。そのうえ、異様な威厳があって、参議でも両手を畳について話し、目を見ながら話をする者がなかったと、長庶子の西郷菊次郎が語り残している。その最も特徴的な巨目を薩摩弁で呼んだのが「うどめ」であり、「うどめどん」が訛ったのが「うーとん」であろう。

身体的特徴

肖像

大久保利通ら維新の立役者の写真が多数残っている中、西郷は自分の写真が無いと明治天皇に明言している。現在のところ西郷の写真は確認されていない。

死後に西郷の顔の肖像画は多数描かれているが、全ての肖像画及び銅像の基になったと言われる絵(エドアルド・キヨッソーネ作)は、比較的西郷に顔が似ていたといわれる実弟の西郷従道の顔の上半分、従弟・大山巌の顔の下半分を合成して描き、親戚関係者の考証を得て完成させたものである。キヨッソーネ自身は西郷との面識が一切無かったが、キヨッソーネは上司であった得能良介を通じて多くの薩摩人と知り合っており、得能の娘婿であった西郷従道とも親しくしていたため、西郷を知る人の意見が取り入れられた満足のいく肖像画になっているのではないかと言われている[17]。

なお、西郷が明治天皇や坂本龍馬や桂小五郎、勝海舟といった維新頃の人物と集団撮影したと称されている写真(通称・フルベッキ写真)が存在するが、西郷は当時すでに肥満しており、この写真で西郷とされている人物のように痩躯ではなかった。また、その他様々な点からこの写真は別の来歴を持つ写真であることが証明されている。

思想

- 「敬天愛人」

- 「道は天地自然の物にして、人は之を行ふものなれば、天を敬するを目的とす。天は人も我も同一に愛し給ふ故、我を愛する心を以て人を愛するなり」[18]

- 「児孫のために美田を買わず」

- 「人を相手にせず、天を相手にして、おのれを尽くして人を咎めず、我が誠の足らざるを尋ぬべし」

- 「急速は事を破り、寧耐は事を成す」

- 「己を利するは私、民を利するは公、公なる者は栄えて、私なる者は亡ぶ」

- 「人は、己に克つを以って成り、己を愛するを以って敗るる」

- 「命もいらず、名もいらず、官位も金もいらぬ人は、始末に困るものなり。この始末に困る人ならでは、艱難をともにして国家の大業は成し得られぬなり」

- 人間がその知恵を働かせるということは、国家や社会のためである。だがそこには人間としての「道」がなければならない。電信を設け、鉄道を敷き、蒸気仕掛けの機械を造る。こういうことは、たしかに耳目を驚かせる。しかし、なぜ電信や鉄道がなくてはならないのか、といった必要の根本を見極めておかなければ、いたずらに開発のための開発に追い込まわされることになる。まして、みだりに外国の盛大を羨んで、利害損得を論じ、家屋の構造から玩具にいたるまで、いちいち外国の真似をして、贅沢の風潮を生じさせ、財産を浪費すれば、国力は疲弊してしまう。それのみならず、人の心も軽薄に流れ、結局は日本そのものが滅んでしまうだろう。

持病

- 肥満

- 高島鞆之助の証言では西郷は大島潜居の頃から肥満になったとしているが、沖永良部島流罪当時は痩せこけて死にそうになっていたという。

- 鹿児島は養豚の盛んな地であり、西郷は脂身のついた豚肉が大好物だった。また、甘い物も好物であった。明治6年(1873年)の征韓論当時は肥満を治そうとしてドイツ人医師ホフマンの治療を受けていた。

- 治療方法は2種用いられていた。一つは蓖麻子油(ひましゆ)を下剤として飲む方法であり、もう一つは運動をする方法であった。後者については『池上四郎家蔵雑記』(市来四郎『石室秘稿』所収、国立国会図書館蔵)中の池上四郎宛彭城中平書簡にこの治療期間中に西郷先生が肥満の治療のために狩猟に出かけて留守だと書いている。

- フィラリア

- 西郷隆盛は、流刑先の沖永良部島で、風土病のバンクロフト糸状虫という寄生虫に感染したとされ、この感染の後遺症である象皮症を患っていた。これによって陰嚢が人の頭大に腫れ上がっていた。そのため晩年は馬に乗ることができず、もっぱら駕篭を利用していた。

- 西南戦争後の、首の無い西郷の死体を本人のものと特定させたのは、この巨大な陰嚢である[19]。ただし、比較的近年に至るまでバンクロフト糸状虫によるフィラリア感染症は九州南部を中心に日本各地に見られ、疫学的には必ずしも感染地を沖永良部島には特定できない。明治44年(1911年)の段階の陸軍入隊者の感染検査で、鹿児島県九州本島部分出身者の感染率は4%を超えていたし、北は青森県まで感染者が確認されている[20]。

先生の肥大は、始めからじゃ無い。何でも大島で幽閉されて居られてからだとのことじゃ。戦争に行つても、馬は乗りつぶすので、馬には乗られなかった。長い旅行をすると、股摺(またず)れが出来る。少し長道をして帰られて、掾(えん)などに上るときは、パァ々々云つて這(は)つて上られる態が、今でも見える様ぢや。斯んなに肥つて居られるで、着物を着ても、身幅が合わんので、能く無恰好な奴を出すので大笑だった。[21]

逸話

- 幼少期、近所に使いで水瓶(豆腐と言う説もある)を持って歩いている時に、物陰に隠れていた悪童に驚かされた時、西郷は水瓶を地面に置いた上で、心底、驚いた表現をして、その後何事も無かったかのように水瓶を運んで行った。

- 西郷は狩猟も漁(すなどり)も好きで、暇な時はこれらを楽しんでいる。自ら投げ網で魚をとるのは薩摩の下級武士の生活を支える手段の一つであるので、少年時代からやっていた。狩猟で山野を駆けめぐるのは肥満の治療にもなるので晩年まで最も好んだ趣味でもあった。西南戦争の最中でも行っていたほどであり、その傾倒ぶりが推察される。したがって猟犬を非常に大切にした。東京に住んでいた時分は自宅に犬を数十頭飼育し、家の中は荒れ放題だったという。

- 坂本龍馬を鹿児島の自宅に招いた際、自宅は雨洩りがしていた。夫人の糸子が「お客様が来られると面目が立ちません。雨漏りしないように屋根を修理してほしい」と言ったところ、西郷は「今は日本中の家が雨漏りしている。我が家だけではない」と叱ったため、隣室で休んでいた龍馬は感心したという。

- 青年、壮年期においては妻のほか愛人を囲うなど享楽的な側面も見せた。祇園の芸妓だった君尾の回想をまとめた『維新侠艶録』や勝海舟の『氷川清話』によると、肥満の女性が好みで、そのエピソードは歌舞伎の演目『西郷と豚姫』でも今に伝わっている。しかし、晩年は禁欲的な態度に徹した。

- 郷土の名物、黒豚の肉が大好物だったが、特に好んでいたのが今風でいう肉入り野菜炒めと豚骨と呼ばれる鹿児島の郷土料理であったことが、愛加那の子孫によって『鹿児島の郷土料理』という書籍に載せられている。

- 沖永良部島は台風・日照りなど自然災害が多いところであったが絶海の孤島だったので、災害が起きたときは自力で立ち直る以外に方法がなかった。そのことを知った西郷は『社倉趣意書』を書いて義兄弟になっていた間切横目(巡査のような役)の土持政照に与えた。社倉はもともと朱熹の建議で始められたもので、飢饉などに備えて村民が穀物や金などを備蓄し、相互共済するもので、江戸時代には山崎闇斎がこの制度の普及に努めて農村で広く行われていた。若い頃から朱子学を学び、また郡方であった西郷は職務からして、この制度に詳しかったのであろう。この西郷の『社倉趣意書』は土持が与人となった後の明治3年(1870年)に実行にうつされ、沖永良部社倉が作られた。この社倉は明治32年(1899年)に解散するまで続けられたが、明治中期には20,000円もの余剰金が出るほどになったという。この間、飢饉時の救恤(きゅうじゅつ)の外に、貧窮者の援助、病院の建設、学資の援助など、島内の多くの人々の役にたった。解散時には西郷の記念碑と土持の彰徳碑、及び「南洲文庫」の費用に一部を充てた外は和泊村と知名村で2分し、両村の基金となった。

- 西郷隆盛が士族兵制論者か徴兵制支持者なのか、当時の政府関係者ですら意見が分かれており、谷干城や鳥尾小弥太は前者を、平田東助は後者であったとする見解を採っている。御親兵導入の経緯などからすれば、士族兵制論者と見るのが妥当であるが、山縣有朋の失脚後も西郷は山縣の徴兵制構想をそのまま継続させたことから、親兵・近衛を通じて形成された山縣に対する西郷の個人的信頼から徴兵令実施を受け入れたと考えられている。ちなみに廃藩置県導入の際に西郷を最終的に同意させたのも山縣であった。

- 晩餐会の席で「作法を知らない」と言って、スープ皿を手に持ってスープを飲み干すなど、飾らない西郷の人柄を、明治天皇はとても気に入っていたと言われる。

- 没年月日(1877年9月24日)がグレゴリオ暦なので、一部の西郷研究者からは生年月日も天保暦からグレゴリオ暦に直して1828年1月23日にすべきだと言う声も上がっている。

伝説

- 西郷星の出現

-

- 西南戦争後も西郷は生存

- 西南戦争後も西郷は中国大陸に逃れて生存しているという風聞が広まっていた。明治24年(1891年)にロシア皇太子(後のニコライ2世)が来日し、鹿児島へも立ち寄ると、西郷が皇太子と共に帰国するという風説もあった。大津事件を起こした津田三蔵は西南戦争に下士官として従軍しており、西南戦争での栄光がなくなると思い、凶行に及んだといわれている。

- 台湾に西郷の子孫あり

- 嘉永4年(1851年)、薩摩藩主・島津斉彬より台湾偵察の密命を受け、若き日の西郷隆盛は、台湾北部基隆から小さな漁村であった宜蘭県蘇澳鎮南方澳に密かに上陸、そこで琉球人を装って暮らした。およそ半年で西郷は鹿児島に帰るが、南方澳で西郷の世話をして懇ろの仲になっていた娘(平埔族)が程なく男児を出産した。この西郷の血筋は孫(呉亀力と伝わる)の代で絶えたという。

系譜