『武士道 Bushido 』-新渡戸稲造(Inazo Nitobé)-

Chapter 09

(The Duty of Loyalty 「忠義」人は何のために死ねるか)

Bushido, the Soul of Japan by Inazo Nitobe

[Book]

[reading]

・Chapter TOP 新渡戸稲造(Inazo Nitobé)TOP

・Chapter 00(Prefaces 序文)

・Chapter 01(Bushido as an Ethical System 武士道とは)

・Chapter 02(Sources of Bushido 武士道の源)

・Chapter 03(Rectitude or Justice 「義」)

・Chapter 04(Courage, the Spirit of Daring and Bearing 「勇」)

・Chapter 05(Benevolence, the Feeling of Distress 「仁」)

・Chapter 06(Politeness 「礼」)

・Chapter 07(Veracity or Truthfulness 「誠」)

・Chapter 08(Honor 「名誉」)

・Chapter 09(The Duty of Loyalty 「忠義」)

・Chapter 10(Education and Training of a Samurai 武士は何を学びどう己を磨いたか)

・Chapter 11(Self-Control 人に勝ち己に勝つために)

・Chapter 12(The Institutions of Suicide and Redress 「切腹」)

・Chapter 13(The Sword, the Soul of the Samurai 「刀」)

・Chapter 14(The Training and Position of Woman 武士道が求めた女性の理想像)

・Chapter 15(The Influence of Bushido 「大和魂」)

・Chapter 16(Is Bushido Still Alive? 武士道は蘇るか)

・Chapter 17(The Future of Bushido 武士道から何を学ぶか)

・[修養]、

・[自警録]

which was the key-stone making feudal virtues a symmetrical arch. Other virtues feudal morality shares in common with other systems of ethics, with other classes of people, but this virtue—homage and fealty to a superior—is its distinctive feature. I am aware that personal fidelity is a moral adhesion existing among all sorts and conditions of men,—a gang of pickpockets owe allegiance to a Fagin; but it is only in the code of chivalrous honor that Loyalty assumes paramount importance.

In spite of Hegel's criticism that the fidelity of feudal vassals, being an obligation to an individual and not to a Commonwealth, is a bond established on totally unjust principles, a great compatriot of his made it his boast that personal loyalty was a German virtue. Bismarck had good reason to do so, not because the Treue he boasts of was the monopoly of his Fatherland or of any single nation or race, but because this favored fruit of chivalry lingers latest among the people where feudalism has lasted longest. In America where "everybody is as good as anybody else," and, as the Irishman added, "better too," such exalted ideas of loyalty as we feel for our sovereign may be deemed "excellent within certain bounds," but preposterous as encouraged among us. Montesquieu complained long ago that right on one side of the Pyrenees was wrong on the other, and the recent Dreyfus trial proved the truth of his remark, save that the Pyrenees were not the sole boundary beyond which French justice finds no accord. Similarly, Loyalty as we conceive it may find few admirers elsewhere, not because our conception is wrong, but because it is, I am afraid, forgotten, and also because we carry it to a degree not reached in any other country. Griffis was quite right in stating that whereas in China Confucian ethics made obedience to parents the primary human duty, in Japan precedence was given to Loyalty. At the risk of shocking some of my good readers, I will relate of one "who could endure to follow a fall'n lord" and who thus, as Shakespeare assures, "earned a place i' the story."

Philosophy of History (Eng. trans. by Sibree), Pt. IV, Sec. II, Ch. I.

Religions of Japan.

The story is of one of the purest characters in our history, Michizané, who, falling a victim to jealousy and calumny, is exiled from the capital. Not content with this, his unrelenting enemies are now bent upon the extinction of his family. Strict search for his son—not yet grown—reveals the fact of his being secreted in a village school kept by one Genzo, a former vassal of Michizané. When orders are dispatched to the schoolmaster to deliver the head of the juvenile offender on a certain day, his first idea is to find a suitable substitute for it. He ponders over his school-list, scrutinizes with careful eyes all the boys, as they stroll into the class-room, but none among the children born of the soil bears the least resemblance to his protégé. His despair, however, is but for a moment; for, behold, a new scholar is announced—a comely boy of the same age as his master's son, escorted by a mother of noble mien. No less conscious of the resemblance between infant lord and infant retainer, were the mother and the boy himself. In the privacy of home both had laid themselves upon the altar; the one his life,—the other her heart, yet without sign to the outer world. Unwitting of what had passed between them, it is the teacher from whom comes the suggestion.

Here, then, is the scape-goat!—The rest of the narrative may be briefly told.—On the day appointed, arrives the officer commissioned to identify and receive the head of the youth. Will he be deceived by the false head? The poor Genzo's hand is on the hilt of the sword, ready to strike a blow either at the man or at himself, should the examination defeat his scheme. The officer takes up the gruesome object before him, goes calmly over each feature, and in a deliberate, business-like tone, pronounces it genuine.—That evening in a lonely home awaits the mother we saw in the school. Does she know the fate of her child? It is not for his return that she watches with eagerness for the opening of the wicket. Her father-in-law has been for a long time a recipient of Michizané's bounties, but since his banishment circumstances have forced her husband to follow the service of the enemy of his family's benefactor. He himself could not be untrue to his own cruel master; but his son could serve the cause of the grandsire's lord. As one acquainted with the exile's family, it was he who had been entrusted with the task of identifying the boy's head. Now the day's—yea, the life's—hard work is done, he returns home and as he crosses its threshold, he accosts his wife, saying: "Rejoice, my wife, our darling son has proved of service to his lord!"

"What an atrocious story!" I hear my readers exclaim,—"Parents deliberately sacrificing their own innocent child to save the life of another man's." But this child was a conscious and willing victim: it is a story of vicarious death—as significant as, and not more revolting than, the story of Abraham's intended sacrifice of Isaac. In both cases it was obedience to the call of duty, utter submission to the command of a higher voice, whether given by a visible or an invisible angel, or heard by an outward or an inward ear;—but I abstain from preaching.

The individualism of the West, which recognizes separate interests for father and son, husband and wife, necessarily brings into strong relief the duties owed by one to the other; but Bushido held that the interest of the family and of the members thereof is intact,—one and inseparable. This interest it bound up with affection—natural, instinctive, irresistible; hence, if we die for one we love with natural love (which animals themselves possess), what is that? "For if ye love them that love you, what reward have ye? Do not even the publicans the same?"

In his great history, Sanyo relates in touching language the heart struggle of Shigemori concerning his father's rebellious conduct. "If I be loyal, my father must be undone; if I obey my father, my duty to my sovereign must go amiss." Poor Shigemori! We see him afterward praying with all his soul that kind Heaven may visit him with death, that he may be released from this world where it is hard for purity and righteousness to dwell.

Many a Shigemori has his heart torn by the conflict between duty and affection. Indeed neither Shakespeare nor the Old Testament itself contains an adequate rendering of ko, our conception of filial piety, and yet in such conflicts Bushido never wavered in its choice of Loyalty. Women, too, encouraged their offspring to sacrifice all for the king. Ever as resolute as Widow Windham and her illustrious consort, the samurai matron stood ready to give up her boys for the cause of Loyalty.

Since Bushido, like Aristotle and some modern sociologists, conceived the state as antedating the individual—the latter being born into the former as part and parcel thereof—he must live and die for it or for the incumbent of its legitimate authority. Readers of Crito will remember the argument with which Socrates represents the laws of the city as pleading with him on the subject of his escape. Among others he makes them (the laws, or the state) say:—"Since you were begotten and nurtured and educated under us, dare you once to say you are not our offspring and servant, you and your fathers before you!" These are words which do not impress us as any thing extraordinary; for the same thing has long been on the lips of Bushido, with this modification, that the laws and the state were represented with us by a personal being. Loyalty is an ethical outcome of this political theory.

I am not entirely ignorant of Mr. Spencer's view according to which political obedience—Loyalty—is accredited with only a transitional function. It may be so. Sufficient unto the day is the virtue thereof. We may complacently repeat it, especially as we believe that day to be a long space of time, during which, so our national anthem says, "tiny pebbles grow into mighty rocks draped with moss." We may remember at this juncture that even among so democratic a people as the English, "the sentiment of personal fidelity to a man and his posterity which their Germanic ancestors felt for their chiefs, has," as Monsieur Boutmy recently said, "only passed more or less into their profound loyalty to the race and blood of their princes, as evidenced in their extraordinary attachment to the dynasty."

Principles of Ethics, Vol. I, Pt. II, Ch. X.

Political subordination, Mr. Spencer predicts, will give place to loyalty to the dictates of conscience. Suppose his induction is realized—will loyalty and its concomitant instinct of reverence disappear forever? We transfer our allegiance from one master to another, without being unfaithful to either; from being subjects of a ruler that wields the temporal sceptre we become servants of the monarch who sits enthroned in the penetralia of our heart. A few years ago a very stupid controversy, started by the misguided disciples of Spencer, made havoc among the reading class of Japan. In their zeal to uphold the claim of the throne to undivided loyalty, they charged Christians with treasonable propensities in that they avow fidelity to their Lord and Master. They arrayed forth sophistical arguments without the wit of Sophists, and scholastic tortuosities minus the niceties of the Schoolmen. Little did they know that we can, in a sense, "serve two masters without holding to the one or despising the other," "rendering unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's and unto God the things that are God's." Did not Socrates, all the while he unflinchingly refused to concede one iota of loyalty to his daemon, obey with equal fidelity and equanimity the command of his earthly master, the State? His conscience he followed, alive; his country he served, dying. Alack the day when a state grows so powerful as to demand of its citizens the dictates of their conscience!

Bushido did not require us to make our conscience the slave of any lord or king. Thomas Mowbray was a veritable spokesman for us when he said:

"Myself I throw, dread sovereign, at thy foot.

My life thou shalt command, but not my shame.

The one my duty owes; but my fair name,

Despite of death, that lives upon my grave,

To dark dishonor's use, thou shalt not have."

A man who sacrificed his own conscience to the capricious will or freak or fancy of a sovereign was accorded a low place in the estimate of the Precepts. Such an one was despised as nei-shin, a cringeling, who makes court by unscrupulous fawning or as chô-shin, a favorite who steals his master's affections by means of servile compliance; these two species of subjects corresponding exactly to those which Iago describes,—the one, a duteous and knee-crooking knave, doting on his own obsequious bondage, wearing out his time much like his master's ass; the other trimm'd in forms and visages of duty, keeping yet his heart attending on himself. When a subject differed from his master, the loyal path for him to pursue was to use every available means to persuade him of his error, as Kent did to King Lear. Failing in this, let the master deal with him as he wills. In cases of this kind, it was quite a usual course for the samurai to make the last appeal to the intelligence and conscience of his lord by demonstrating the sincerity of his words with the shedding of his own blood.

Life being regarded as the means whereby to serve his master, and its ideal being set upon honor, the whole

Read文献、

book文献

TOP

日本の魂ー日本思想の解明ー

日本的思考の根源を見る。

”忠義”は追従ではない。”名誉”は求める心である。

(第三章 義-あるいは正義について)

サムライにとって、 卑怯な行動や不正な行動ほど恥ずべきものはない。

(第九章 忠義)

武士道は、われわれの良心を主君の奴隷となすべきことを要求しなかった

(第十章 武士の教育)

武士道は経済とは正反対のものである。それは貧しさを誇る。

(第十一章 克己)

心の奥底の思いや感情—特に宗教的なもの—を雄弁に述べ立てることは、日本人の間では、それは深遠でもなく、 誠実でもないことの疑いないしるしだと受け取られた。

(第十四章 女性の教育と地位)

妻がその夫、家庭そして家族のために身を捨てることは、男が主君と国のために身を捨てるのと同様、自発的かつみごとになされた。

|

・新渡戸稲造

第1弾「世界を結ぶ『志』~新渡戸稲造の生涯~」、

第2弾「未来につながる『道』~新渡戸稲造の武士道~」、

第3弾「すべてに根ざす『愛』~新渡戸稲造の苦悩~」、

・ 新渡戸稲造の至極の名言集

・「新渡戸稲造の名言」20話

| |

・Bushido: The Soul of Japan by Inazo Nito(1-18)

・Bushido: The Soul of Japan by Inazo Nitobe(1-18)

・武士道「BUSHIDO」Japanese Ver.

・≪AI朗読≫武士道

・【武田鉄矢】『武士道』完全版

|

Bushido, the Soul of Japan

『武士道は定式化されたものではないが、昔もそして今も、日本人を鼓舞し、わが国を動かす原動力なのである』

日本人が日本人たりえる所以。

国家としての歴史的哲学体系を持たない日本の、現代社会においても尚、我々の血肉となり、在り続ける道徳律の根幹は「武士道」にあり。

日本人 新渡戸稲造博士が世界に発信した日本人論。

世代と国境を越え今なお読み継がれている世界的ベストセラー。

西洋・東洋の文化・哲学・思想と照らし合わせながら、その特異性と唯一無二の行動規範・心の拠り所を詳細に解説した普遍の書が、完全現代語訳、プロフェッショナルのナレーションで今蘇る。

21世紀。世界第三位の経済大国であるわが国日本。

政治的にも文化的にもより身近に世界と対峙する現代においてこそ、われわれの心の中に脈々と流れ続ける、日本人が日本人足らしめる「武士道」の精神を紐解く時なのではないだろうか。

本書は1世紀の時を超えた今も尚色褪せること無く、むしろその博識と見解、交える事例とそのユーモアに溢れた表現により現代人の我々にも実に痛快に日本の心「武士道」を理解させてくれる。

「武士道」がいつどのようにして始まったのか、それはどんな特徴を持ち、どのようなことを教えようとしているのか、武士以外の一般民衆にどのような影響を与えたのか、その影響がどれほど永く続いているか。

様々な角度・キーワードで武士の心得、さむらいの心の在り方をリレー形式で綴っている。

世界有数の犯罪率の低さ、大災害時での規律、自発的な他助の精神と行動は時代を超えて、親から子へと語り継がれてきた「道徳律」が存在し続けていることを如実に表している。

知っているようで知らない「日本の心」が、ここに明かされている。

内容抜粋

「今何とおっしゃいましたか?」と敬愛する教授は尋ねた。

「日本の学校には宗教の教育がないということでしょうか?」

そうですと答えると、教授は驚いて足を止めた。そして、今でも耳から離れない声音で、重ねてこう聞いた。

「宗教がない! だとしたら、いったいどうやって道徳を教えるんですか?」

この質問に私は意表を突かれ、とっさに答えを返すことができなかった。というのも、子どもの頃私が学んだ道徳というのは、学校で教わったものではなかったからである。私は、自分の持っている善悪正邪の概念を作り上げているさまざまな要素をひとつひとつ分析してみて、ようやく、それらを私の中に植えつけたのは「武士道」であったことに気づいた。

武士道とは、武士が守るよう求められる、もしくは、そう教えられる道徳的な作法である。文字に書かれたものはなく、せいぜい口伝えで伝えられた格言や、有名な武士や学者が書いたものが残されている程度である。

多くの場合そうしたものさえなく、しかしだからこそかえって深く心に刻まれ、守るべき掟<<おきて>>として強い拘束力を持っていた。ひとりの優秀な頭脳が考え出したものでもなければ、ひとりの高名な人物の生きかたが手本となってできたものでもない。数十年、数百年に及ぶ武士の歴史の中で自然に醸成されたものである。

「義は、道理に従ってためらうことなく、何をなすべきかを決断する力である。死ぬべきときは死を選び、討つべきときには討つことを選ぶ力である」

「戦いの真っただ中に飛び込んで討ち死にするのはいともたやすいことで、身分の卑しい者にもできる。生きるべきときは生き、死ぬべきときにのみ死ぬのが本当の勇気である」

「義に過ぎれば固くなる。仁に過ぎれば弱くなる」

「礼法の要点は精神を養うことにある。礼をもって静かに座っていれば、どんな乱暴者でも危害を加える気になれないほどに」

仁愛や謙譲の精神から生まれた礼儀は、他人に対する思いやりから生まれて、人への同情心を品よく優雅に表現するものだからである。

「心だに誠の道にかないなば祈らずとても神や守らん」

「忠ならんと欲すれば孝ならず、孝ならんと欲すれば忠ならず」

命は主君に仕えるための手段だと考えらえており、その理想形は、名誉のために命を捨てることであった。

「おのれの魂という畑が、優しい心で揺れ動くのを感ずるか? まかれた種が芽吹こうとしているのだ。言葉でそれを妨げてはならぬ。静かに、ひそやかに、自ら芽吹くのを見守っているのだ」

「死を軽<<かろ>>んずることは勇気のいる行為である。しかし、生きることが死よりもつらいときに、あえて生きることこそが本物の勇気である」

「かくすればかくなるものと知りながら やむにやまれぬ大和魂」

目次

訳者序文

初版への序文

改訂第10版への序文

新渡戸博士の『武士道』に寄せて

第1章 道徳体系としての「武士道」

第2章 武士道の源

第3章 「義」――あるいは正義について

第4章 「勇」――勇敢さと忍耐力

第5章 「仁」――慈愛の心

第6章 「礼」

第7章 「誠」――正直さと誠実さ

第8章 「誉<<ほまれ>>」――あるいは名誉について

第9章 「忠義」

第10章 武士の教育と鍛錬

第11章 自制心

第12章 切腹と敵討ちという制度

第13章 刀――武士の魂

第14章 女性の教育と地位

第15章 武士道から大和魂へ

第16章 武士道は今も生きているか

第17章 武士道のこれから

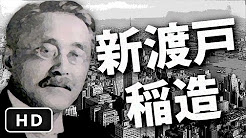

新渡戸稲造(Inazo Nitobe)

文久2年(1862年)、藩士 新渡戸十次郎の三男として南部藩(今の岩手県)に生まれる。

幼少期より東京英語学校に学び、少年期は、後に「代表的日本人」の著者でもある内村鑑三らとともに札幌農学校へ入学し学業を磨いた。

明治維新後はアメリカ・ドイツに渡り農政学を始め様々な研究に従事。

台湾総督府技師として台湾の殖産に携わり功績を挙げる。

国際連盟事務次長としても国際的に活躍。帰国後は様々な学校の教職を歴任した後、東京女子大学初代学長にもなる。

本書「武士道」は英語のみならずポーランド、ドイツ、ノルウェー、スペイン、ロシア、イタリアなど、主として欧米の多様な国の言語に翻訳され世界的ベストセラーとなる。旧五千円札の肖像画の人物としても有名。

TOP

朗読,Read 朗読,Read

|

朗読,Read

朗読,Read

朗読,Read

朗読,Read