『武士道 Bushido 』-新渡戸稲造(Inazo Nitobé)-

Chapter 17

(The Future of Bushido 武士道の遺産から何を学ぶか)

Bushido, the Soul of Japan by Inazo Nitobe

[Book]

[reading]

・Chapter TOP 新渡戸稲造(Inazo Nitobé)TOP

・Chapter 00(Prefaces 序文)

・Chapter 01(Bushido as an Ethical System 武士道とは)

・Chapter 02(Sources of Bushido 武士道の源)

・Chapter 03(Rectitude or Justice 「義」)

・Chapter 04(Courage, the Spirit of Daring and Bearing 「勇」)

・Chapter 05(Benevolence, the Feeling of Distress 「仁」)

・Chapter 06(Politeness 「礼」)

・Chapter 07(Veracity or Truthfulness 「誠」)

・Chapter 08(Honor 「名誉」)

・Chapter 09(The Duty of Loyalty 「忠義」)

・Chapter 10(Education and Training of a Samurai 武士は何を学びどう己を磨いたか)

・Chapter 11(Self-Control 人に勝ち己に勝つために)

・Chapter 12(The Institutions of Suicide and Redress 「切腹」)

・Chapter 13(The Sword, the Soul of the Samurai 「刀」)

・Chapter 14(The Training and Position of Woman 武士道が求めた女性の理想像)

・Chapter 15(The Influence of Bushido 「大和魂」)

・Chapter 16(Is Bushido Still Alive? 武士道は蘇るか)

・Chapter 17(The Future of Bushido 武士道から何を学ぶか)

・[修養]、

・[自警録]

whose days seem to be already numbered. Ominous signs are in the air, that betoken its future. Not only signs, but redoubtable forces are at work to threaten it.

Few historical comparisons can be more judiciously made than between the Chivalry of Europe and the Bushido of Japan, and, if history repeats itself, it certainly will do with the fate of the latter what it did with that of the former. The particular and local causes for the decay of Chivalry which St. Palaye gives, have, of course, little application to Japanese conditions; but the larger and more general causes that helped to undermine Knighthood and Chivalry in and after the Middle Ages are as surely working for the decline of Bushido.

One remarkable difference between the experience of Europe and of Japan is, that, whereas in Europe when Chivalry was weaned from Feudalism and was adopted by the Church, it obtained a fresh lease of life, in Japan no religion was large enough to nourish it; hence, when the mother institution, Feudalism, was gone, Bushido, left an orphan, had to shift for itself. The present elaborate military organization might take it under its patronage, but we know that modern warfare can afford little room for its continuous growth. Shintoism, which fostered it in its infancy, is itself superannuated. The hoary sages of ancient China are being supplanted by the intellectual parvenu of the type of Bentham and Mill. Moral theories of a comfortable kind, flattering to the Chauvinistic tendencies of the time, and therefore thought well-adapted to the need of this day, have been invented and propounded; but as yet we hear only their shrill voices echoing through the columns of yellow journalism.

Principalities and powers are arrayed against the Precepts of Knighthood. Already, as Veblen says, "the decay of the ceremonial code—or, as it is otherwise called, the vulgarization of life—among the industrial classes proper, has become one of the chief enormities of latter-day civilization in the eyes of all persons of delicate sensibilities." The irresistible tide of triumphant democracy, which can tolerate no form or shape of trust—and Bushido was a trust organized by those who monopolized reserve capital of intellect and culture, fixing the grades and value of moral qualities—is alone powerful enough to engulf the remnant of Bushido. The present societary forces are antagonistic to petty class spirit, and Chivalry is, as Freeman severely criticizes, a class spirit. Modern society, if it pretends to any unity, cannot admit "purely personal obligations devised in the interests of an exclusive class." Add to this the progress of popular instruction, of industrial arts and habits, of wealth and city-life,—then we can easily see that neither the keenest cuts of samurai's sword nor the sharpest shafts shot from Bushido's boldest bows can aught avail. The state built upon the rock of Honor and fortified by the same—shall we call it the Ehrenstaat or, after the manner of Carlyle, the Heroarchy?—is fast falling into the hands of quibbling lawyers and gibbering politicians armed with logic-chopping engines of war. The words which a great thinker used in speaking of Theresa and Antigone may aptly be repeated of the samurai, that "the medium in which their ardent deeds took shape is forever gone."

Norman Conquest, Vol. V, p. 482.

Alas for knightly virtues! alas for samurai pride! Morality ushered into the world with the sound of bugles and drums, is destined to fade away as "the captains and the kings depart."

If history can teach us anything, the state built on martial virtues—be it a city like Sparta or an Empire like Rome—can never make on earth a "continuing city." Universal and natural as is the fighting instinct in man, fruitful as it has proved to be of noble sentiments and manly virtues, it does not comprehend the whole man. Beneath the instinct to fight there lurks a diviner instinct to love. We have seen that Shintoism, Mencius and Wan Yang Ming, have all clearly taught it; but Bushido and all other militant schools of ethics, engrossed, doubtless, with questions of immediate practical need, too often forgot duly to emphasize this fact. Life has grown larger in these latter times. Callings nobler and broader than a warrior's claim our attention to-day. With an enlarged view of life, with the growth of democracy, with better knowledge of other peoples and nations, the Confucian idea of Benevolence—dare I also add the Buddhist idea of Pity?—will expand into the Christian conception of Love. Men have become more than subjects, having grown to the estate of citizens: nay, they are more than citizens, being men.

Though war clouds hang heavy upon our horizon, we will believe that the wings of the angel of peace can disperse them. The history of the world confirms the prophecy the "the meek shall inherit the earth." A nation that sells its birthright of peace, and backslides from the front rank of Industrialism into the file of Filibusterism, makes a poor bargain indeed!

When the conditions of society are so changed that they have become not only adverse but hostile to Bushido, it is time for it to prepare for an honorable burial. It is just as difficult to point out when chivalry dies, as to determine the exact time of its inception. Dr. Miller says that Chivalry was formally abolished in the year 1559, when Henry II. of France was slain in a tournament. With us, the edict formally abolishing Feudalism in 1870 was the signal to toll the knell of Bushido. The edict, issued two years later, prohibiting the wearing of swords, rang out the old, "the unbought grace of life, the cheap defence of nations, the nurse of manly sentiment and heroic enterprise," it rang in the new age of "sophisters, economists, and calculators."

It has been said that Japan won her late war with China by means of Murata guns and Krupp cannon; it has been said the victory was the work of a modern school system; but these are less than half-truths. Does ever a piano, be it of the choicest workmanship of Ehrbar or Steinway, burst forth into the Rhapsodies of Liszt or the Sonatas of Beethoven, without a master's hand? Or, if guns win battles, why did not Louis Napoleon beat the Prussians with his Mitrailleuse, or the Spaniards with their Mausers the Filipinos, whose arms were no better than the old-fashioned Remingtons? Needless to repeat what has grown a trite saying that it is the spirit that quickeneth, without which the best of implements profiteth but little. The most improved guns and cannon do not shoot of their own accord; the most modern educational system does not make a coward a hero. No! What won the battles on the Yalu, in Corea and Manchuria, was the ghosts of our fathers, guiding our hands and beating in our hearts. They are not dead, those ghosts, the spirits of our warlike ancestors. To those who have eyes to see, they are clearly visible. Scratch a Japanese of the most advanced ideas, and he will show a samurai. The great inheritance of honor, of valor and of all martial virtues is, as Professor Cramb very fitly expresses it, "but ours on trust, the fief inalienable of the dead and of the generation to come," and the summons of the present is to guard this heritage, nor to bate one jot of the ancient spirit; the summons of the future will be so to widen its scope as to apply it in all walks and relations of life.

It has been predicted—and predictions have been corroborated by the events of the last half century—that the moral system of Feudal Japan, like its castles and its armories, will crumble into dust, and new ethics rise phoenix-like to lead New Japan in her path of progress. Desirable and probable as the fulfilment of such a prophecy is, we must not forget that a phoenix rises only from its own ashes, and that it is not a bird of passage, neither does it fly on pinions borrowed from other birds. "The Kingdom of God is within you." It does not come rolling down the mountains, however lofty; it does not come sailing across the seas, however broad. "God has granted," says the Koran, "to every people a prophet in its own tongue." The seeds of the Kingdom, as vouched for and apprehended by the Japanese mind, blossomed in Bushido. Now its days are closing—sad to say, before its full fruition—and we turn in every direction for other sources of sweetness and light, of strength and comfort, but among them there is as yet nothing found to take its place. The profit and loss philosophy of Utilitarians and Materialists finds favor among logic-choppers with half a soul. The only other ethical system which is powerful enough to cope with Utilitarianism and Materialism is Christianity, in comparison with which Bushido, it must be confessed, is like "a dimly burning wick" which the Messiah was proclaimed not to quench but to fan into a flame. Like His Hebrew precursors, the prophets—notably Isaiah, Jeremiah, Amos and Habakkuk—Bushido laid particular stress on the moral conduct of rulers and public men and of nations, whereas the Ethics of Christ, which deal almost solely with individuals and His personal followers, will find more and more practical application as individualism, in its capacity of a moral factor, grows in potency. The domineering, self-assertive, so-called master-morality of Nietzsche, itself akin in some respects to Bushido, is, if I am not greatly mistaken, a passing phase or temporary reaction against what he terms, by morbid distortion, the humble, self-denying slave-morality of the Nazarene.

Christianity and Materialism (including Utilitarianism)—or will the future reduce them to still more archaic forms of Hebraism and Hellenism?—will divide the world between them. Lesser systems of morals will ally themselves on either side for their preservation. On which side will Bushido enlist? Having no set dogma or formula to defend, it can afford to disappear as an entity; like the cherry blossom, it is willing to die at the first gust of the morning breeze. But a total extinction will never be its lot. Who can say that stoicism is dead? It is dead as a system; but it is alive as a virtue: its energy and vitality are still felt through many channels of life—in the philosophy of Western nations, in the jurisprudence of all the civilized world. Nay, wherever man struggles to raise himself above himself, wherever his spirit masters his flesh by his own exertions, there we see the immortal discipline of Zeno at work.

Bushido as an independent code of ethics may vanish, but its power will not perish from the earth; its schools of martial prowess or civic honor may be demolished, but its light and its glory will long survive their ruins. Like its symbolic flower, after it is blown to the four winds, it will still bless mankind with the perfume with which it will enrich life. Ages after, when its customaries shall have been buried and its very name forgotten, its odors will come floating in the air as from a far-off unseen hill, "the wayside gaze beyond;"—then in the beautiful language of the Quaker poet,

"The traveler owns the grateful sense

Of sweetness near he knows not whence,

And, pausing, takes with forehead bare

The benediction of the air."

Read文献、

book文献

TOP

日本の魂ー日本思想の解明ー

日本的思考の根源を見る。

”忠義”は追従ではない。”名誉”は求める心である。

(第三章 義-あるいは正義について)

サムライにとって、 卑怯な行動や不正な行動ほど恥ずべきものはない。

(第九章 忠義)

武士道は、われわれの良心を主君の奴隷となすべきことを要求しなかった

(第十章 武士の教育)

武士道は経済とは正反対のものである。それは貧しさを誇る。

(第十一章 克己)

心の奥底の思いや感情—特に宗教的なもの—を雄弁に述べ立てることは、日本人の間では、それは深遠でもなく、 誠実でもないことの疑いないしるしだと受け取られた。

(第十四章 女性の教育と地位)

妻がその夫、家庭そして家族のために身を捨てることは、男が主君と国のために身を捨てるのと同様、自発的かつみごとになされた。

|

・新渡戸稲造

第1弾「世界を結ぶ『志』~新渡戸稲造の生涯~」、

第2弾「未来につながる『道』~新渡戸稲造の武士道~」、

第3弾「すべてに根ざす『愛』~新渡戸稲造の苦悩~」、

・ 新渡戸稲造の至極の名言集

・「新渡戸稲造の名言」20話

| |

・Bushido: The Soul of Japan by Inazo Nito(1-18)

・Bushido: The Soul of Japan by Inazo Nitobe(1-18)

・武士道「BUSHIDO」Japanese Ver.

・≪AI朗読≫武士道

・【武田鉄矢】『武士道』完全版

|

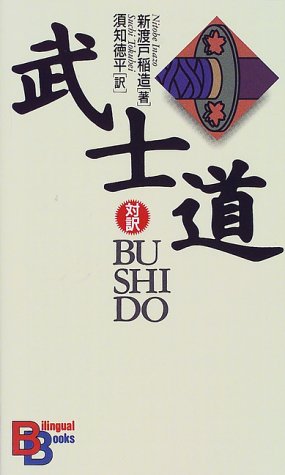

Bushido, the Soul of Japan

『武士道は定式化されたものではないが、昔もそして今も、日本人を鼓舞し、わが国を動かす原動力なのである』

日本人が日本人たりえる所以。

国家としての歴史的哲学体系を持たない日本の、現代社会においても尚、我々の血肉となり、在り続ける道徳律の根幹は「武士道」にあり。

日本人 新渡戸稲造博士が世界に発信した日本人論。

世代と国境を越え今なお読み継がれている世界的ベストセラー。

西洋・東洋の文化・哲学・思想と照らし合わせながら、その特異性と唯一無二の行動規範・心の拠り所を詳細に解説した普遍の書が、完全現代語訳、プロフェッショナルのナレーションで今蘇る。

21世紀。世界第三位の経済大国であるわが国日本。

政治的にも文化的にもより身近に世界と対峙する現代においてこそ、われわれの心の中に脈々と流れ続ける、日本人が日本人足らしめる「武士道」の精神を紐解く時なのではないだろうか。

本書は1世紀の時を超えた今も尚色褪せること無く、むしろその博識と見解、交える事例とそのユーモアに溢れた表現により現代人の我々にも実に痛快に日本の心「武士道」を理解させてくれる。

「武士道」がいつどのようにして始まったのか、それはどんな特徴を持ち、どのようなことを教えようとしているのか、武士以外の一般民衆にどのような影響を与えたのか、その影響がどれほど永く続いているか。

様々な角度・キーワードで武士の心得、さむらいの心の在り方をリレー形式で綴っている。

世界有数の犯罪率の低さ、大災害時での規律、自発的な他助の精神と行動は時代を超えて、親から子へと語り継がれてきた「道徳律」が存在し続けていることを如実に表している。

知っているようで知らない「日本の心」が、ここに明かされている。

内容抜粋

「今何とおっしゃいましたか?」と敬愛する教授は尋ねた。

「日本の学校には宗教の教育がないということでしょうか?」

そうですと答えると、教授は驚いて足を止めた。そして、今でも耳から離れない声音で、重ねてこう聞いた。

「宗教がない! だとしたら、いったいどうやって道徳を教えるんですか?」

この質問に私は意表を突かれ、とっさに答えを返すことができなかった。というのも、子どもの頃私が学んだ道徳というのは、学校で教わったものではなかったからである。私は、自分の持っている善悪正邪の概念を作り上げているさまざまな要素をひとつひとつ分析してみて、ようやく、それらを私の中に植えつけたのは「武士道」であったことに気づいた。

武士道とは、武士が守るよう求められる、もしくは、そう教えられる道徳的な作法である。文字に書かれたものはなく、せいぜい口伝えで伝えられた格言や、有名な武士や学者が書いたものが残されている程度である。

多くの場合そうしたものさえなく、しかしだからこそかえって深く心に刻まれ、守るべき掟<<おきて>>として強い拘束力を持っていた。ひとりの優秀な頭脳が考え出したものでもなければ、ひとりの高名な人物の生きかたが手本となってできたものでもない。数十年、数百年に及ぶ武士の歴史の中で自然に醸成されたものである。

「義は、道理に従ってためらうことなく、何をなすべきかを決断する力である。死ぬべきときは死を選び、討つべきときには討つことを選ぶ力である」

「戦いの真っただ中に飛び込んで討ち死にするのはいともたやすいことで、身分の卑しい者にもできる。生きるべきときは生き、死ぬべきときにのみ死ぬのが本当の勇気である」

「義に過ぎれば固くなる。仁に過ぎれば弱くなる」

「礼法の要点は精神を養うことにある。礼をもって静かに座っていれば、どんな乱暴者でも危害を加える気になれないほどに」

仁愛や謙譲の精神から生まれた礼儀は、他人に対する思いやりから生まれて、人への同情心を品よく優雅に表現するものだからである。

「心だに誠の道にかないなば祈らずとても神や守らん」

「忠ならんと欲すれば孝ならず、孝ならんと欲すれば忠ならず」

命は主君に仕えるための手段だと考えらえており、その理想形は、名誉のために命を捨てることであった。

「おのれの魂という畑が、優しい心で揺れ動くのを感ずるか? まかれた種が芽吹こうとしているのだ。言葉でそれを妨げてはならぬ。静かに、ひそやかに、自ら芽吹くのを見守っているのだ」

「死を軽<<かろ>>んずることは勇気のいる行為である。しかし、生きることが死よりもつらいときに、あえて生きることこそが本物の勇気である」

「かくすればかくなるものと知りながら やむにやまれぬ大和魂」

目次

訳者序文

初版への序文

改訂第10版への序文

新渡戸博士の『武士道』に寄せて

第1章 道徳体系としての「武士道」

第2章 武士道の源

第3章 「義」――あるいは正義について

第4章 「勇」――勇敢さと忍耐力

第5章 「仁」――慈愛の心

第6章 「礼」

第7章 「誠」――正直さと誠実さ

第8章 「誉<<ほまれ>>」――あるいは名誉について

第9章 「忠義」

第10章 武士の教育と鍛錬

第11章 自制心

第12章 切腹と敵討ちという制度

第13章 刀――武士の魂

第14章 女性の教育と地位

第15章 武士道から大和魂へ

第16章 武士道は今も生きているか

第17章 武士道のこれから

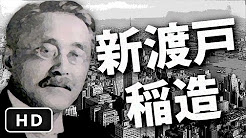

新渡戸稲造(Inazo Nitobe)

文久2年(1862年)、藩士 新渡戸十次郎の三男として南部藩(今の岩手県)に生まれる。

幼少期より東京英語学校に学び、少年期は、後に「代表的日本人」の著者でもある内村鑑三らとともに札幌農学校へ入学し学業を磨いた。

明治維新後はアメリカ・ドイツに渡り農政学を始め様々な研究に従事。

台湾総督府技師として台湾の殖産に携わり功績を挙げる。

国際連盟事務次長としても国際的に活躍。帰国後は様々な学校の教職を歴任した後、東京女子大学初代学長にもなる。

本書「武士道」は英語のみならずポーランド、ドイツ、ノルウェー、スペイン、ロシア、イタリアなど、主として欧米の多様な国の言語に翻訳され世界的ベストセラーとなる。旧五千円札の肖像画の人物としても有名。

TOP

朗読,Read 朗読,Read

|

朗読,Read

朗読,Read

朗読,Read

朗読,Read